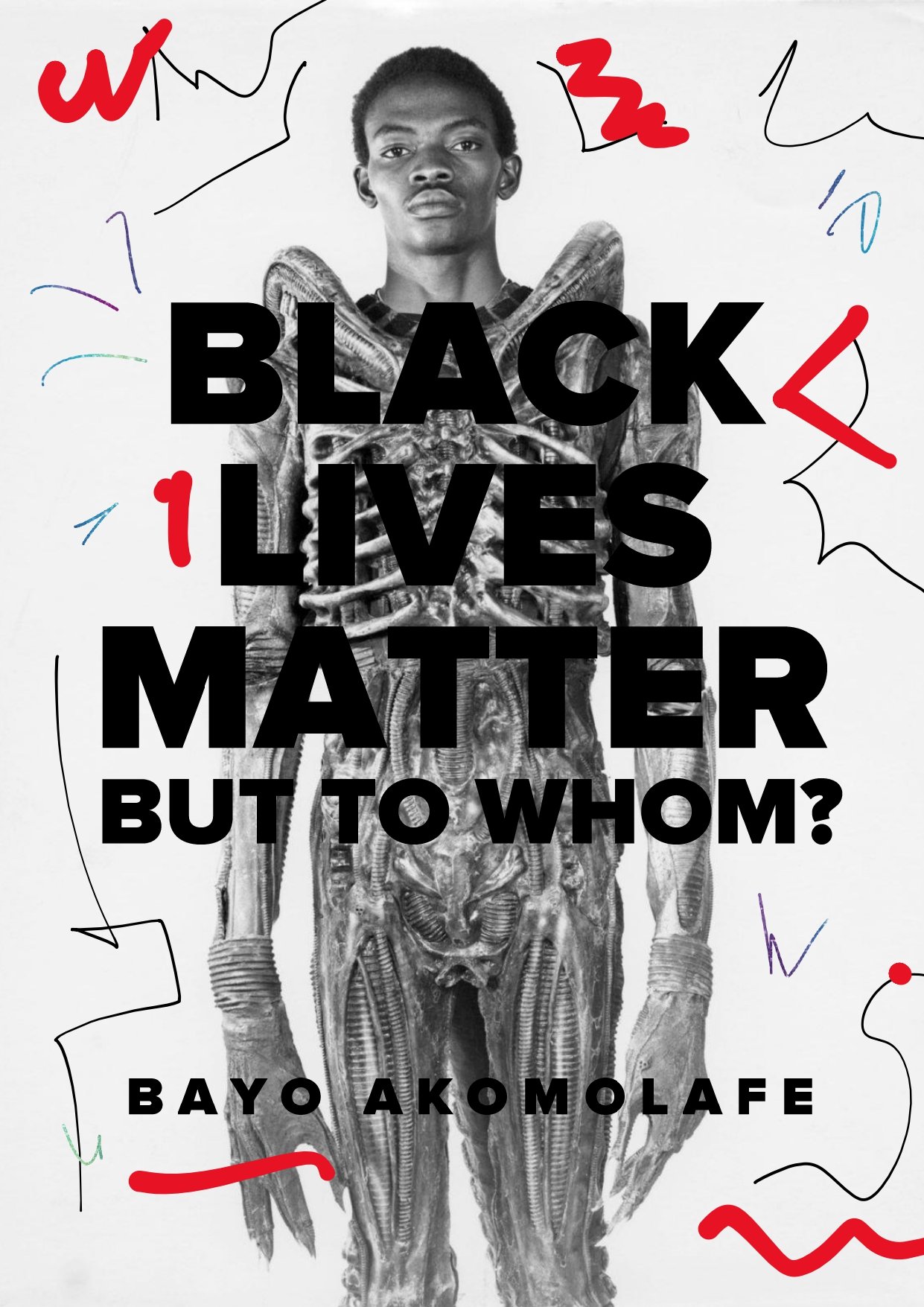

Black lives matter, But to whom? Why We Need a Politics of Exile in a Time of Troubling Stuckness (Part II)

Exiling the visibility trap – beyond justice

If you fashion your emancipation using the materials of your oppression, using the same epistemological frameworks of your incarceration, you risk reinforcing your oppression.

It may be reassuring to the justice-seeking efforts of BLM to imagine that the thrust of politics is to overwhelm the racists, to educate them out of their hatred, to address systematic oppression so that Black individuals might thrive, but the individual, the traditionalist human subject, is already a form of genocide. [25] This genocide is not some distant event in the past, but an ongoing reproduction of the ‘world’ as ‘clearing’ – a cutting off the ways we are imbricated with ecological matterings that coincides with the killing fields of industrial gentrification and with the asylum captivity that is named, ‘the Human’.

In asserting that “when Black people get free, everybody gets free”, BLM does not consider how ‘freedom’ – the pixelated promise of the surface – is, like the oppressed thing in le Guin’s ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’, already a racialized shutting away of the haunted public, the Black outdoors populated by bones and ancestral beads and ghosts and little critters screaming for help in wet wardrobes and residential schools. Freedom is the hope for disembarkation, the myth of arrival, the slushy idea that seems innocuous at first but then travels when one least expects it and builds a parking lot where there was once a sacred mountain.

Freedom won’t do. We need a new problem. New bodies. New rituals. Exquisite, creolized subjectivities that erupt from affiliations with monstrous cracks. Turning into obsidian birds. Freedom, this disliberal subjectivity and its neurotypical commitments to permanence, visibility, categoricity, transcendence, recognizable borders, comportment, and stability, assumes too much. Covers too much. Flattens too much. This freedom is the powder-wigged renovation of the wilds, an installation of the stable self in the middle of the concrete sprawl.

The fugitive point here, worth revisiting and dancing along with its straying lines, is that the politics that cradles minoritarian demands to be recognized and seen by their dominant others is a trap. As Smith and his colleagues explain it in their article about becoming invisible, “the dangers of pursuing identities as safeguards against insecurity and contingency… derive from the compromises that are necessary within the institutions that produce and sustain these identities… [T]he key task is to avoid reproducing institutions and forms of thinking which configure thought and action in predictable ways.” [26]

If justice is tethered to efforts to save the hypothetical “Subject X”, the marginalized subject, the infinitely multiplying Other who needs to be acknowledged, embraced, affirmed, and recognized, and for whom any refusal to adhere to strict protocols of encounter reportedly constitutes ‘harm’, we risk a politics that functions as a “problematic reinvestment in the humanist subject” – a politics that isn’t so much an attending to the excluded as it is a production of the eternally excluded, a necessary prerequisite for a politics devoted to intersectional inclusion and powered by the self-referentiality of the ‘centre’. [27] The intersectionality that proliferates newer identities as already excluded, potentially vulnerable populations, and as candidates for inclusion, risks dampening the experimentation that could potentially reinvigorate politics.

But shouldn’t we seek justice?

Shouldn’t we demand accountability for the murder of Black bodies on the streets of a nation whose founding notion is the freedom of all God’s children; for the systematic exclusion of Black lives from better standards of living; for the discovery of the bones of ‘Bakhita’ – the slave girl from Africa – in Rio de Janeiro; for the dark histories of public health, the Tuskegee experiments, and the medical apartheid enacted by the Euro-American scientific complex in its unauthorized dissections and robbing of dead Black people; for the 11 million lives taken from the continent of Africa and transplanted to the so-called New World; for the algorithmic robbing of African nations using Trojan loans and austerity measures to siphon resources away from people who need them; for the ways Black people have been represented as bestial, animalistic, incapable, and phantasmagorical objects of White fascination; for the exhibition and abuse of Sarah Baartman, the Khoikhoi woman whose generous hips troubled the erotic dreams of her 19th century European captors and led them to lock her up in the circus?

In more recent times, the collective aspirations for the righteous return of the so-called ‘Benin Bronzes’ – a cache of invaluable artefacts, commemorative sculptures, and sacred relationships masterfully carved in brass plaques and other media, looted by a British retaliatory military force in 1897 after the ransacking of the old Benin Kingdom (in present day Nigeria) – have found some success. Disturbed by the energetic exertions of African scholars, movements for repatriation, and activists like the Congolese pan-African “Robin Hood of Restitution Activism”, [28] Mwazulu Diyabanza – whose newsworthy antics in recalcitrant European museums and headstrong insistence that African artefacts be restored to their peoples led to many fines, court appearances, and prison sentences – the once-resolute dam of western stonewalling negligence gave way to a forceful tide of shifting public sentiments, leading Germany to declare in 2021 – the first to do so – that it would permanently return its collection of the priceless pieces from German museums to Nigerian institutions. [29]

Last December (2022), a number of those Bronzes arrived in Nigeria “amid laughter, tears, and some audible frustration with the ongoing silence of the country that first stole them.” [30]

“The objects from the haul of treasures known as the Benin bronzes, including a brass head of an oba (king), a ceremonial ada and a throne depicting a coiled-up python, were taken from the sacked city during a British punitive expedition in 1897 and later sold to German museums in Berlin, Hamburg, Stuttgart and Cologne.

Shortly after lunchtime on Tuesday, Germany’s foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, passed perhaps the most spectacular of the returned objects into the gloved hands of Nigeria’s culture minister, Lai Mohammed.

‘She comes back to where she belongs,’ Baerbock said as she handed over a miniature mask of the Iyoba (queen Mother), made of ivory and decorated with yellow glass pearls, red coral and a crown of stylised electric catfish, which was looted from the bedchamber of the last independent oba.” [31]

When I read the story of the long-prayed-for return of those pieces to my country, I experienced the emotional equivalent of what I can only describe as a relieving sigh rudely terminated by a loud burp. A mix of joy and trepidation. A quizzical longing for the devil lurking between the lines. My contentless suspicions, seeking sanctuary, soon found an anchorhold in the body of the report, further down the page:

“With presidential elections coming up in Nigeria in 10 weeks’ time, the potential for Germany to use the artworks as a diplomatic bargaining chip is limited. Economic ties between Africa’s and Europe’s largest economies by GDP are less developed than they could be, with German businesses concerns about corruption one obstacle for investment. Transparency International’s last corruption index has the west African state at number 154 out of 180 countries.

The Benin bronzes that have returned to Nigeria are meant to be eventually put on display at a new pavilion in Benin City, which Germany is co-financing with €4m.

Currently still only a few holes in the red soil of a plot of land, the pavilion is expected to opened in 2024 and supposed to form the apex of a new cultural centre that would support restitution projects in other African countries. Fundraising for a new Edo museum of west-African art, designed by the Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye, is scheduled to start after the pavilion’s opening.” [32] (Emphasis mine)

Hidden behind the fanfare around the eminent return of the Benin Bronzes, behind the soaring sounds of victory, behind the rhetoric of justice realized, behind the lights and the cameras and the essays colourfully commemorating a moral moment – something worth celebrating after all the grey weather and dampening news stories about pandemics and Eastern European wars – behind all of that was the troubling codicil of ‘return’. You see, the hidden curriculum of repatriation is that it deploys colonial maps to locate, reinscribe, and reinforce hegemonic territoriality – broadening the reach of its project of intelligibility under the guise of moral awakenings. Slushy entanglements working invisibly in the unspoken and insensibly dense depths beneath victory-so-called.

The ‘objects’ might just as well have been moved from one holding bay to another department within the same German museum. By transferring the ‘objects’ from their ownership to a new, multi-million-euro museum [33] and archaeological project in Edo State, which they had partially funded, the German authorities inadvertently made it certain that the ‘objects’ would remain captive to the visual regimes of the modern industrial world. [34]

A cursory search for the terms of the new agreement that would play host to the long exiled ‘objects’, weary after a century and a quarter away from the lands that birthed them, would reveal that the newly planned collection centre, EMOWAA (Edo Museum of West African Art), [35] was the end-result of a series of negotiations between sneakily under-the-radar stakeholders in Nigeria (under the name, ‘Legacy Restoration Trust’) and a network of Museum curators in Europe – including the British Museum, which also put its cash in the pot to help realize the dream for a new African renaissance. The computer-generated images of the museum to come, like a Wakandan wet dream, depicted happy, vaguely African children staring at the repatriated pieces – which were now at ‘home’, behind glass boxes that ontologically protected them from the infiltration of touch.

But at least, they were home.

Perhaps my description of this news story unfairly paints its actors with sinister motives. What else is there to do with the Benin Bronzes? What else could we possibly expect from Hamburg and London? What is wrong with glass boxes, museums, and respectful negotiations with local governments? What more is there to notice if not this landing place that is justice? Shouldn’t we at least celebrate the good-enough small measures taken to address the multi-generational loss of the Benin people?

This is neither a story about good vanquishing evil nor an attempt to cast the efforts of its principal actors as conspiratorially malicious or perpetually insufficient – in the ways that cultural critic Rey Chow names the significatory incarceration of an intersectional politics devoted not only to the production of the perpetually excluded but to the privileging of the perpetually offended. In many respects, this is justice. This is good work. There is probably nothing more to be done. This is what many have hoped to see happen in their lifetimes: the brass bodies that once knew the fierce and approving worship of Oba Ovonramwen and his chiefs returned to the dust that summoned them. This is justice. This is good.

But that’s the matter at issue here: good is an intelligible point within a moral economy that prohibits other realities from showing up. Justice is a worlding event, [36] a concerted exercise in the constitutional exclusion of other ontological possibilities for living and dying, a node of criss-crossing agencies and crystallized concepts functional for a moment. Something is always left out in the way justice worlds the world. Something lurks. In this instance of repatriation, the antipodal tensions between old colonial states and their former territories reinscribes the terms that hegemonic powers are familiar with. The cartographies of capture coincide with the cartographies of restoration like two hands coming together in applause, the applause of justice. The moral slushiness thickens, reproducing its subjects and their subservience, firming up the global nation-state order, occluding the stories that flirt with the scandalous possibility that the ‘Benin Bronzes’ are not and have never been ‘objects’.

When Killian Fox of The Economist wrote in April 2020 that the British Museum was being haunted, [37] the world was only just beginning to experience the full force of a planet in pushback mode…a planet that was curiously more alive, more agential, more intelligent than modern imagination allows for it to be. Reporting about floating orbs, alarm-triggering sculptures, self-opening doors, and frightened museum guards who spoke anonymously about the unexplainable restlessness of the 9 million assorted ‘objects’ in their care and their nightly groanings and stirrings and doings, Fox wrote:

“Even without visitors, the museum is never completely silent. The main building, which dates back to the 1820s and has been expanded and reconfigured ever since, is alive with creaks, as old buildings are prone to be. The air-conditioning hums. Doors clank. Sudden breezes whistle around corners and up lift shafts. As security guards move through the 94 rooms open to the public, along the rabbit warren of back-of-house offices and passageways, and into the rambling network of storage facilities below ground, they are privy to the building’s most intimate sounds: scrapes and groans, drowned out during opening hours, can grow disconcertingly loud at night.

The guards are accustomed to such disturbances. But every so often a patrol encounters a noise, a flash of movement, or simply a sudden lurch in the pit of the stomach, that stops even hardened veterans in their tracks.” [38]

The stories that follow Fox’s gripping opening (my favourite being the account of a wooden, Congolese two-headed dog that sets off the fire alarms in the gallery whenever anyone points at it) would make Toy Story, Pixar’s award-winning animated feature about toys that play dead when their owners show up and do things when they turn away, a studious documentary and theoretically dense account about the hidden lives of ‘objects’. Something about the outrageous restlessness of a world that moves away from its categoricity, away from the unblemished purity of its cache number and archival habitation disturbs the choreography of ‘return’; mourns the loss of situated relations that could never be replaced by transferring images within the same moral economy; brackets justice as the managerial logistics of capture and the manufacture of subjectivities; hints at the occult passing of the deep insensible; touches a multisensorial, transcorporeal worlding beyond the prickly borders of the “right-thing-to-do”; and, perhaps gestures at a different politics – one characterized by the taking on of new postures, becoming invisible, playing host to new senses, and experimenting with losing one’s way.

‘Return’ is problematic. Going back to some originary point presumes not only that the universe is populated with stable points, but that the human individual – ennobled with some transcendent wayfinding rationality, perhaps the kind that inspired Norse goddess Frigga to shut down the realms to save her doomed son Baldur – is uniquely capable of performing this choreography of return. The act presumes things are ‘objects’, hylomorphic recipients of the significatory order humans imprint upon them.

It is not the case that we shouldn’t desire justice. One cannot speak that way when one sees morality as immanent, open-ended, and profusely materialistic. There is no superintending “should” to dictate what to do. But this doesn’t mean there aren’t architectural imperatives secreted by specific stabilities. To the extent that humans are entangled with the world – not just relational but relations concretized – the question of what to do and how to do it will always be shrouded, showing up only partially, never fully available for full scrutiny. We will act-together-with the territorial-ecological-moral constraints that swirl and sigh and spill and soar. Then through those movements in their transversality, cracks will show up – opening up new spaces for something else to materialize. Something invisible to the computational, glass-holding logic of justice.

Do Black lives need justice? Yes. I suppose so. I also suppose one must give the flying bird a perch to rest its avian body, as another Igbo proverb goes – even though I am acutely aware that the perch is a place of slaughter, a beguiling invitation to the trap of visibility.

Justice is a mode of anticipation, a relationship of rectilinear transactions to gods or their avatars. One needs to be erect for justice to apply. One needs to register one’s face – but, you see, the state needs Black backs just as much as it needs our faces. The very future of statehood depends on inclined black bodies. Such is the double-edged conceit of justice: to guarantee the smooth running of the public, it must maintain the paradigm of the citizen. And to maintain the paradigm of the citizen, it must reify the vagabond, the fugitive, the monster at the edges. More than Black bodies needing justice, justice needs Black bodies as avatars of the monstrous, memories of bare lands, warnings to the state of things to keep things moving. Or else. Justice promises the glories of rectilinearity while standing on the bent backs of its necessary props. Not that justice is evil – but that it too is embodied, contextual, limited, and material.

And yet, that which makes Black bodies eminently killable, that which eats Black bodies up and vomits them back up, only to eat them again, the transmogrified memory of the insensible…the paraontological and the ontofugitive [39] masquerading as the monster, as the criminal, as the Nigerian prince, as the dangerous devil at the crossroads, is the trace of an elsewhere, an elsewhen, a dis/human Great Dismal Swamp at some remove from the rhizomatic cottonfields of our ongoing protests. Not a utopian arrival. Not a new manifesto. Not the “Planet Black-Black” that American comedian Greer Barnes jokes about. [40] I mean to say that the place where Black bodies fall is a place of many treasures. Black failure – the boots on Black faces, the potholes on Black streets, the pressing of Black bones into the earth – potentializes radical transformation.

Let me say a little more about that last point: I do not mean to suggest that ‘Black’ bodies or the precarity of racialized suffering somehow encodes social transformation. Indeed, when we say someone is ‘Black’, [41] we are reigniting and retracing an image contemporaneous with colonial appellations. The image has utility – a utility granted it by its imbrications within a network of relations. It is this utility that is suspect. What we want to be alive to are non-utilitarian lines snaking away from the violence of Black appellation. Ontogenesis [42] exceeds identity: we want to spill beyond the captivity of being seen.

Black identity is not a strategy for emancipation. It has proven to be a useful strategy for compromise. We convene around melanated traces and heterogenous experiences to weave a unified, prescriptive narrative that forces our claims to the state, and then we hope for reforms generous enough to include us in state-sponsored freedoms. The trouble with that is – again – the freedoms we seek are ironic recapitulations of our subservience. We would need a different notion of blackness – a non-identitarian one that gestures towards larger fields of mattering, that notices the ecologically vibrant ways bodies are mediated and modulated and oriented and activated beyond identity.

This spillage is a becoming-black. Not a becoming ‘Black’, but a becoming ‘black’. A becoming-monster. A losing one’s way. A veering off-course. A becoming-imperceptible. It is not necessarily about building new institutions, winning legislative victories, receiving reparations, or gaining greater representation and visibility. The becoming-black I speak of is an experimentation with new sensorial affinities, new subjectivities, new intelligences. It is a threshold of postures that some bodies, Black-identified or otherwise, may have some proximity to as a result of specific sociomaterial arrangements. [43]

The blackness I speak of is a neuro-indeterminacy (preceding neurodiversity and typicality). Becoming-black crystallizes as neurodiversity, inviting a politics of experimentation, of accompaniment, of peripheral (or rather, peri-feral) animacy – not enforcement. This blackness has no other. It is not a state of being, an identity, a phase, a stable point to reach. It is the ongoingness of things that dramatically releases White coloniality from its burden of naming everything. It is the immanent virtuality that maddens the individual.

I want to go beyond the ways Black agitation and activism reinscribe the imperatives of rectitude. Beyond critique. I want to make the case for a different idea of blackness – the one that roams, the ‘principle’ of darkness that offers no apologies for its refusal to be illuminated. I am tired of critique alone – for critiquing the shortcomings of white modernity can quickly become a strategy for survival within white modernity and an attempt to wrest the reins of power from its present drivers. I offer a dark illumination of failure, a notion of blackness (this time with a small ‘b’, too molecular to be concerned with identity) as a site of excess, fugitivity as a comely heuristic and cartography for navigating the stickiness of contestation politics and walking away as theoretically generative in its capacity to help cultivate a politics of becoming invisible.

In short, I want to make the case for failure, the monster’s failure – a generative incapacitation – as a strategy of emancipation, of approach, not arrival. I want to make the case for blackness as the dramaturgical life of individuation in the context of white coloniality – the seditious streaming of bodies without organs, an autistic murmuration, the anarranging lines that disturb stable identitarian distinctions, black mattering, an aesthetic without objects [44] or fixed subjects, an ontological apostasy. blackness, this refusal to capitalize the first letter of the sentence, muddies the syntax, andmessesupreadabilityasitgestures towards invisibility.

The invisibility of the monster.

The Monstrous Errancy of Black Mattering

Immediately accompanied by a forebodingly deep and gravelly hum, the video flickers on, revealing an octagonal hallway with walls lined with white pads and clinical lights, the makeshift interior of a spacefaring vessel. At the end of the hallway, a dark figure emerges, first the semblance of a hand, then the rest of a menacingly otherworldly sticklike figure. Catatonic and yet full of grace, it approaches us with claws curled into gnarly existential questions. It ambles through the tube with impossibly long legs, taking small creeping steps towards the screen like a praying mantis; risking exposure but not quite managing to escape the shroud of darkness that clings to it; pausing often to look around as it swivels its long phallic skull arching away from the taut lines of its muscly, totemic body. [45]

It’s the alien. And it needs to be seen to be believed. Or rather, to see it is to be distorted beyond belief.

In 1979, Bolaji Badejo leapt from a private test screening to become the alien. Ridley Scott’s fantastic alien. The Xenomorph. Complete with searing acid blood, insect-like morphology, and a raping proboscis-like mouth that inseminated its prey with the unspeakable.

How Badejo became the least celebrated occupant of film’s arguably most evocative monster is the stuff of novels – and beyond the scope of this essay, now in its third act. A few details about the performer and his short-lived career as the Xenomorph – necessary to this account of the monster, the black mattering cordoned off by Black excellence – will suffice.

Bolaji Badejo was a 26-year-old Nigerian student in London, the son of an affluent family in Lagos – and, as such, in many respects, a Nigerian prince in stature and substance – when he was approached in a pub in Soho and invited to inhabit the monstrous frames of Swiss artist H. R. Giger’s twisted dreams. To that untimely and unexpected invitation, he said – quite characteristically – “Okay.” And ‘inhabit it’ he did. His otherworldly 6-foot-10-inch frame slipped into the elegantly murderous obsidian black of Ridley Scott’s alien figure, perhaps cinema’s most prestigious monster.

Through endless hours of cosmetic application, training in Tai-chi, and mastering the gliding moves of the Xenomorph, Badejo became a terrifying presence on set.

"‘The idea,’ Badejo told Cinefantastique, ‘was that the creature was supposed to be graceful as well as vicious, requiring slow, deliberate movements. But there was some action I had to do pretty quick. I remember having to kick Yaphet Kotto, throw him against the wall, and rush up to him. Veronica Cartwright was really terrified. After I fling Yaphet Kotto back with my tail, I turn to go after her, there’s blood in my mouth, and she was incredible. It wasn’t acting. She was scared.’" [46]

In the movie, Badejo’s lone and fully grown alien haunts, rapes, and eventually slaughters the crewmembers of the fictional ‘USCSS Nostromo’, an interstellar hauler vehicle constructed in 2101 and redeployed by the Weyland-Yutani Corporation to “investigate and hopefully recover a potential Xenomorph specimen from the moon, placing the crew ten months away from Earth” after it was redirected from an original mission out of Neptune.

Seeded in the body of a venturesome crewmember via a “facehugger” (an earlier life cycle stage in the metamorphosis of a Xenomorph), who is then carried back into the ship in a gross violation of quarantine protocols, the alien stalks the lower engineering decks, evading detection due to faulty security cameras rendered inoperable by damage from landing on the strange planet. [47]

The alien’s morphology is of great interest to me: described as “a perfect organism” with a “structural perfection matched only by its hostility”, the creature acts like a parasitoid, “rather than a technical parasite, because it spends a good portion of its life untethered to a host.” [48] Its dominant move is to infect its prey with its own progeny, instead of killing its captive.

“Rather than feed on humans, xenomorphs often incapacitate prey and transport them to the hive to impregnate the still-live humans with their young. If a particular human reacts violently or doesn’t make a suitable host for the growing young, the xenomorph simply kills that human and moves on.” [49]

In iconic close-up shots of this sequence of impregnation/murder, the alien leans close, as if courting its prey, its saliva-engulfed lips quivering menacingly as it slowly opens its mouth, allowing a phallic probe to quickly ‘punctuate’ the prey’s presumptuous boundaries. The film’s producers confirm that the way the Xenomorph uses humans is designed to inspire sexual horror and trouble male viewers: “It could just as easily fuck you before it killed you, [which] made it all the more disconcerting.” [50]

At the end of filming and promotion interviews, Bolaji Badejo returned to Nigeria, set up an art studio, and fathered two children before succumbing to sickle cell anemia on the 22nd of December 1992. He was 39. His iconic turn as the Xenomorph is his only credited film role.

However, to those curious enough about the many coincidences that connect Giger’s beast with a certain Yoruba god, Èsù, whose trickster antics and monstrous shapeshifting indeterminacy have been implicated in the dramaturgy of white coloniality and black mattering, Badejo – himself of Yoruba descent – may have accidentally played two monsters simultaneously and, in so doing, embodied a radical politics that whispers seditiously today. [51]

First, it is incredibly difficult not to see how Giger’s overtly sexual design of the Xenomorph mimics cultural representations of Èsù – who is all phallus and almost nothing else. In multiple stories and depictions of the go-between trickster Òrìsà from Nigeria, Èsù’s head (ogó) is a large penis that runs along his back, erect and tense. Èsù has a penis in the expected place as well; it is his many penises that explain how he inseminates everything, invading our notions of separation, breaking binaries, raping lines, exposing us to the fecundity of a universe that does not think in terms of Newtonian points and straight geometries. For Èsù, everything is a palimpsest, a play of immanence and virtuality. A paragon of femininity, Esu’s principal work is to disturb boundaries, to make borders pregnant with possibility, to bleed independence, to upset the countability of the accountable, to feminize the colonial.

Like the Xenomorph, Èsù mocks identity and is drawn to warm bodies, incubators for new realities. Warm bodies are moving bodies, membranously receptive bodies, ready for touch, for the fever of transformation. I think warm bodies contrast with the coldness of cryopreserved identities in spacefaring vessels. Warmth is the temperature of ontological mutiny.

Even more interesting is how Nostromo, Scott’s adopted name for the hauling ship that is sent by the Weyland Corporation to mine the galaxy and fetch back specimens of alien locals, dramatizes whiteness in its excavatory project of colonial control. The name ‘Nostromo’ was inspired by Scott’s love of English novelist Joseph Conrad’s works. In 1904, Conrad published a novel called ‘Nostromo’. Five years prior, Conrad wrote ‘Heart of Darkness’, a novella popularly known for its troubling depiction of Africa as primitive recipient of European mastery.

The Nostromo ship is the site of the Xenomorph’s feminizing monstrosity, just as the slave ships of the transatlantic trade that came to the African continent were (in Yoruba author, playwright, and scholar Femi Euba’s play, The Gulf) allegedly infiltrated by the trickster Èsù, who – in lieu of supporting Ogun his brother god’s efforts at chasing away the violent colonists – travels with the captives to the New World, living in the lower decks of the ships, eventually creolizing the religions of the North by infecting them with stowaway deities. [52] Instead of fighting back, using the epistemologies of the colonizer, Èsù eats the slave ship, eats the shore, and climbs into the body of the slave driver. There are no traumatic binaries here: no victim and no perpetrator. By implicating himself in the story of captivity, Èsù – like the Xenomorph – implodes the colonial from within, troubling its claims to exclusivity, to noble distance, to sinfulness or sainthood, leaving a messy goo of hybrid bodies in the wake of ‘his’ sexual exploits. [53]

Together with Bolaji Badejo’s ethnicity as a Yoruba man, one wonders if there were other matters at work (storytelling beyond storytellers’ intentions), whether Giger and Scott – politically active designers and filmmakers aware of the troubles of colonial expansion – took inspiration from the Yoruba god to tell a story of infiltration, of the sideways insemination of coloniality by monstrous figures. If this is the case, Alien is not simply and conclusively a film about intrepid human explorers conquering the monstrous galactic wilds: it is about strange encounters, about the unexplored gift of the monster, the fascist exhaustion with the human as a stable/final fixture of the cosmos, the promise of the grotesque, the potency of a certain kind of diss/colonial performance that concerns itself with infiltrating, subverting, and im/mediating colonial permanence. The film is about Èsù.

A theme of the generative monster (living outside the moral compulsions of the haunted and energetically/umbilically entangled with novelty and exquisite otherness) emerges from this double, diffractive reading of ‘Alien’ and Yoruba folklore, of Xenomorph and Èsù, of Nostromo and white civilization, of skull and phallus – rounded out, perhaps, by reports that H. R. Giger legendarily insisted that the Xenomorph be painted ‘Black’, an anecdote that has troubled contemporary analysts of the film and its production, with one article calling it “racist” and “dehumanizing” to Black people. [54]

Without dismissing this speculative attribution of racism to Giger’s most iconic creature, [55] it needs be said that no less colonially violent is the zeitgeist’s effort to sanitize Blackness, to render it presentable, to individuate it along identitarian hegemonic cartographies, to coddle it and make it comfortable, and shield it from being “dehumanized”. Once one learns to bracket “humanity” as the racialized appellation of ‘Blackness’, whose operations are in part responsible for the decapitation of African lands and importation of bodies into the spectrum of the ‘Man’, whose regime christens the Anthropocene, whose legacy is felled trees and parking lots, being ‘dehumanized’ might begin to take on ironically emancipatory accents.

Against the tide of sentiments in this regard, I am plenty wary about contemporary efforts resisting the association of Blackness with monstrosity, with the grotesque, with the stowaway, and the occult. At the very least, Giger, beholding the impossibly tall frame of Èsù’s child, Bolaji Badejo, unintentionally paid a collective non-conscious mytho-psychic tribute to the critical necessity of the monster as the more-than-human release clause from the trap of nobility, white beauty, and modern finality.

When Badejo climbs into the Xenomorph, he climbs into Èsù. He becomes monster. He turns into an unanticipated, late figure in the swirling conversations about where Blackness goes and what to do about the paucity of justice. In an image (easily accessible online with the mere listing of “Bolaji Badejo” as one’s search criteria) that feels symbolic of his unexpectedly potent critique of Black excellence as a rehabilitation of Black bodies, as inclusion, Badejo poses in Xenomorph skin. Only his head seems recognizable, familiar to our senses. His body – everything beneath his neck – sharply deviates from human biology. There is a stoic princely calm to Badejo’s look – as if he were quite content to inhabit the very thing the world says he shouldn’t. His panache would make Kanye West blush. This image is an artefact of a different politics, a thousand-thousand words spoken in the mereness of a Black man inhabiting the monster.

But why is inhabiting the monster so vital a move to make if we must address the slushiness of our protests, the violence of justice, and the ironic containment of our activisms? Why is this a strategic response to Martin Luther King’s “where does Blackness go?” Why is this an invitation to BLM to contest its own adoption of excellence and investigate its tethering to justice?

Let me remind us, repeating themes I’ve begun to develop through the text: Blackness is the hylomorphic imprint of whiteness. Black representation, Black showing up, and Black ascendancy are what is performed by BLM, a performance governed by the logistics of managing dissociated selves. By centring voice. This Blackness collapses at the recognizability of the ableist subject. This is Blackness as an agitational force, whiteness exploring its tensions, a creature of capture, of the fishbowl. What we are “really” saying (beyond saying) when we call for Black lives to matter is for the machinations of subservience to hold us ever so tightly in their grip. And that is risky. What is at stake is a sense of exquisite new subjectivities, other ways of eating, smelling, growing, dreaming, wanting, loving, dying, knowing, listening, travelling, and becoming.

As such, we must find a way of edging towards the rivers at the edges of Georgia where Black bodies become birds. We must put black lives mattering to work within a posthumanist milieu, within an Afrocene. [56] Within black mattering that flows beyond representationalist-humanist-substantialist-identitarian-modernist frameworks.

The only way for Blackness to spill beyond this hegemonic dance of form over matter, of subject over objectified bodies, of master over slave, of neurotypicality over neurodiversity, these relations of colonial superintendence, is to collapse the binary through a different reading of their shared indebtedness to a larger stream of collective becoming. This is Simondon’s transindividuality, Barad’s agential realism, Deleuzio-Guattarian agencement, Bergsonian virtuality, Glissantian opacity, Moten’s fugitivity and Chandler’s paraontology. This is black mattering. This is ontofugitivity. This is the blackness I have already written about. The one that sits uncomfortably in sentences. With the small ‘b’.

The entire question of how Black lives matter – in the sense of a mattering that exceeds the constitutional violence that calls Blackness into its subservient dependence on white centrality – turns on this virtual flow, this animist black mattering.

I’m speaking of ‘blackness’ as a counterhegemonic, posthumanist, more-than-experiential, roaming force that deterritorializes, interfaces, intra-acts, inflects, stows away, upsets, offends, exposes, and disorients. Something that precedes the individual without terminating finally at the individual. [57] I am thinking of black mattering as exceeding the frames of justice, of ascendancy, of excellence, of representation, cutting right to the way modernity fashions bodies – which, by the way, aren’t already there but continually manufactured. It is chiasmic, crossroad-ian, and crippled. It is not identitarian. It is not reducible to Black experiences, Black identities, and Black agendas. It is matter in its monstrosity. A milieu of monsters. A peri-ferality. [58]

Redeploying blackness as flow, as fugitive exile from the entrapments of recognition instituted by the plantation, allows us to think outside of repetition. Allows us to become undone. Allows new vistas to open up. But we could never know about these openings, these generous experimentations with corporeal possibility and political divergence, except by the agency of the monster. Black mattering or (small-b) blackness is the way the monster shows up and the way new worlds erupt.

By the dynamic configurations of white arrangements – through the bone memories of slave encounters, the dark stories of pagan trysts that led the Euro-American wrist to conceive of the term ‘animist’ as a pejorative, through the unspeakable horrors of the Jim Crow South – Blackness is indefinitely associated with monstrosity. Modernity’s nightmare. The exertions of politics have been to extend the benevolence of gentrification towards the swamps of Blackness – to “include” the intruder. Against a politics that seeks to save the beast, I think monstrosity is strangely generative.

I don’t mean each Black-identified person or community is monstrous to white modernity: if we all lost our eyes, then melanated skin would be difficult to rule in as part of that monstrous assemblage that haunts. As such, the monster is not a stable image; it is a how, not a what. This “how” usually includes – as part of its assemblage – Black skin, but this is contingent. I think of the monstrous then as a prim(ordi)al mark, echoes of the frightening roar of emergence, whose lasting and lingering presence (or active absence) becomes a moral-corporeal-territorial-theological edge boundaried by fear, repulsion, recoil, punishment, and rage. White modernity’s radical other or monster is not just the deviant, the vagabond, the criminal, the autistic – it is the shifting already-racialized territoriality and conditionality that produces these errant bodies with varying degrees of rehabilitability.

The monster/monstrous is not an individual, [59] it is an assemblage…the Other written into the cells of the citizen, exploded into the surface, the subaltern shimmering in the spoils of capture. It is psychic-ecological. The monster is the agent of flight and transduction. The monster is imperceptibility. The monster is the paragon of invisibility, not because it cannot be seen but because it queers modes of visuality, rending apart the smooth trafficking of images in their flattened consumptibility. The monster is the program lurking in the image, the anamorphosis of the casual image: the distortion is perspectival, really a critique of subjectivity than any inherent vice.

We are used to thinking of the monster as ‘evil’; images of the corrupted spring to mind when we imagine monstrosity. However, the figure of the monster is more prestigious than our moral predilections for comeliness and familiarity and has long been a multicultural technology for disturbing assemblages and arrangements. The monster is not the thing lurking in the distance; it is a pattern of relations that potentializes and actualizes errancy from hylomorphic relations, from anthropocentric algorithms, from fascist continuity, from image copy, from justice as logistics. The monster is the glitch, a program without designer, an aesthetic of refusal.

What this litany of descriptions hopefully produces is the queer image of the monster as a site of inquiry, an intensity, an invitation to accompany and cultivate failure. Failure is speculative tracing, an experimental sitting with the alien egg our once-pristine citizenship has been exposed to and impregnated with. The task of politics as becoming-black, as a moving beyond justice without necessarily doing away with the need for it, is to sit with/in the crack, [60] to dance, [61] to cultivate ways of tending to this alien thing gestating within. It is to touch the errancy of ‘our’ bodies – a touching that simultaneously undercuts our claims to ownership. It is to ‘follow’ their transcorporeality into the wilderness.

Where Blackness goes is not to a destination, a brand-new city, some Black person’s face on a dollar bill. Where Blackness goes is not a place, a point on the map, a permanence, a what. It is a how. This how is the monstrous, the crack in the citizen. The promise of the monster, of black errancy, swings on the unspeakable worlds that modern subjectivity forecloses in its pretensions to finality – a grim presence festooned with the hieroglyphics of justice, ascendancy, and the inducements of greater representation. By accompanying the zigzagging lines of the monstrous, we might touch justice’s other side; we might come to new relationships with the soil that break our dependence on shopping malls and the poisonous circuits of modern food; we might forge new relationships with dreams, with ancestral dis/continuities, with joy. Like deep biospheres and their teeming populations that do not depend on sunlight, we might find ourselves in abtherapeutic paths of wellbeing that refuse the sanity of suburbia. We might know ourselves in stunningly new ways – as if for the first time.

It doesn’t even have to last. Just a gathering. Just a glimmer of the ecstatic. Just a new word that undoes the shackles of loyalty. Just a sense that magic is not some fool’s errand amid more serious endeavours. Just a voice whispering back in the thick night. Black mattering and the monsters it births are autistic deviations from the traps of infinity – from the insistence that change has to be monolithic. [62] Like justice – an Atlasian figure always holding the world aloft on his shoulders.

Èsù leaves the scene: autistic wander lines

This journey through considerations of the conditions of how Black Lives come to matter as subjects of violence, how Black excellence tends to reinforce the parameters of captivity, how black mattering exceeds the identitarian frames of recognition, and how the monster signals a disorientation and new cartography and politics of emancipation – one released from the cyclical saving of the perpetually excluded subject – must, of necessity, end at the feet of my child, Èsù in a different form, whose tiptoeing sentence-winding exile from the interpersonal dynamics of names and stable things opens out more space for inquiry, for politics, and for the otherwise.

When my son Kyah was just about to turn two, he would retreat to a corner of the room and stack things on top of each other or run them straight in an unending line. He didn’t answer when we called him, and he very often looked like he was going to run into a wall, hit his head, and continue along his silent way as if nothing happened. He slept very little, walked around in circles on his toes, avoided eye contact, cried with every sigh of molecules around him, had ‘strange’ gestures, hardly followed instructions, said no in response to everything, and slowly lost his appetite for everything we took great joy in feeding his older sister.

I had strong suspicions. We soon verified he was on the spectrum. The diagnosis hung like a slow-release poison in my flesh, killing me softly. Something ultimately died in me: the hope that I might have a meaningful father-son relationship with him. In the place of the intimacy that I had hoped to cultivate with him, there lived a wild god whose primal name was “Why?”; he haunted me every time I looked at Kyah, every time his inexplicable tears paralyzed the rest of my family, announcing his name as if to remind me he was still there. Why? Why me?

My fears got the better of me, whispering horrid tales about what might yet be. Somewhere in the terrible midst of these voices, a proposal leaked through the soil with a gripping instruction: fix him. Cure him. Something is wrong here. This wasn’t how it was meant to be.

These voices didn’t belong to some gravelly demons. They were mine, so to speak. And so, against my own training, against my politics and my once convenient views on the autistic and its emancipatory potentials for dislodging ableist notions of normalcy and subjectivity from their central positionings, I read hundreds of papers and articles on the subject – looking for that modality, that new insight in neurobiology, indigenous knowledge systems, homeopathy, anything that could help him.

Soon, it started to occur to me that I was constantly looking past him. I had learned in silent ways that my real son was just a few degrees obscured by the one I had. This became quite clear to me when, one day, when he was four, while shopping with my wife, our daughter and Kyah, he became terribly distressed. Holding his hand, I urged him to be quieter, to control himself, to “use your words.” Kyah’s refusal to be reformed, named, and tamed in the moment escalated into a full-blown ‘event’: he fell to the polished floor, thrashing and flailing, causing quite a stir. I could feel eyes burning into my skin – the colour of which was already a matter of jokes to passers-by in the south Indian city of Chennai. If I were any lighter, the eyes that burned into mark would have left indelible scars. Kyah, oblivious to my deepening frustrations – or perhaps acutely aware of them – wept on the floor. He needed help. I wasn’t sure how to support him.

“Walk away,” my wife, EJ, said to me. She had closed the gap between us and hurried back to meet both of us struggling. Looking me straight in the eye, her voice was still, soft, unwavering, and grounded in a way that immediately assured me it was what needed to happen, she repeated herself. What happened was an understated demonstration of the politics I craved, the one I write about now. Kyah’s mother got on all fours and laid next to him in an accompanying silence that was the gestural equivalent of building an altar to a wild god. Between EJ and I, we painted wildly divergent accounts of Kyah’s autism. In my own portrait of things, Kyah was the wooden Pinocchio in Carlo Collodi’s and Disney’s versions of the story, where the marionette’s father-figure Geppetto longed for him to become a real boy. For EJ, Kyah was already miraculous. He didn’t need to become a ‘real boy’. He didn’t need reforms, a cure, or a fairy’s intervention. In this sense he was unlike Pinocchio, more like Buratino, Aleksei Tolstoy’s 1936 nonconformist reimagination of Collodi’s 1883 original in which the wooden boy doesn’t turn into a ‘real boy’ but retains his wood subjectivity.

EJ’s courage called into question the centrality of ‘real’ or ‘normal’. By accompanying him in his trouble, instead of seeking to close the flailing chasm that had yawned wide in that arena of eyes, she disputed the claims that Kyah’s autism was his. Instead, she asked, with the eloquence of her silence, “why must there be relations of ownership behind autism? Must someone own autism for us to be enlisted, drawn in, and magnetized by autistic effects?” In what sense might we say autism is more-than-brain-based, more than chemicals, more-than-self? Milieu? Perhaps the immediate response to this might be that autism is not some metaphorical state or atmospheric condition; it is embodied in real lives and has been empirically supported by behavioural studies and clinical observations ever since science gained experimental maturity. At issue here is how personhood is rendered, and how individuals come to be. If we think of autistic nonverbal children through the prism of stable selves, already made, each having (or failing to have) a master signifier in the interiority of the person, then we have already eliminated the stunning contingencies that bundle us up with material and molecular flows, technologies and conditions, secretions, and orientations, and animacies too strange to commit to language. To black mattering.

EJ’s gesture of accompaniment inadvertently mimicked French visionary and mis/educator Deligny’s tentatives in the early 60s leading all the way to his death in 1996. He probably would have laid next to EJ and Kyah, tracing a cartography that zigzagged and danced with territories, gesturing at elsewheres embedded in ordinary everyday practice. Like Èsù on a slave ship.

***

Fernand Deligny began cartographic tracing as a practice when an ally and friend, filmmaker Jacques Lin – among those he called ‘close presences’ – working with the network of encampments he had established in the mountainous and desert terrain of Cévennes in 1965, complained about the self-harming habits of the autistic children and teens that lived together in the commune. Deligny reportedly advised Lin to trace maps of these gestures and daily routines, instead of falling into the language of assigning symptoms here and there. Soon, these nonutilitarian ‘maps’, composed by dense place-making lines that did not seek to explain, symbolically represent, reform, productize, or interpret the nonverbal autistic children that lived there, but was instead a form of place-making becoming-with and redrawing of the lines of the human, became the central work of Deligny’s notable attempt to live in the hyphenating crack of nonverbal autism.

He called these cartographic process ‘lignes d’erre’, French for wander lines – lines of errancy, lines of flight. These ‘maps’ were not maps to, maps of, but mappings with/in that ignited the ordinary, and recalibrated the human to cartographies instead of stable subjects within territories.

Deligny was born in 1913, two decades before the Second World War broke out, but like most who would live through the time came to be heavily defined by it. Starting out as a schoolteacher, then later committing himself to working with disabled children, he joined Jean Oury and Felix Guattari in their post-war Institutional Psychotherapy project at La Borde, a psychiatric clinic at Cour-Cheverny in France. He worked with them for just two years, from 1965 – 1967, after which he branched out to create his experiments in living with autism.

Deligny was militantly anti-asylum, anti-institutionalization. He rejected the psychoanalytic categories of thought that alienated autistic children as requiring reform (or as was the case in hospitals during the Vichy era, extermination). I like to imagine Deligny as a Pied Piper figure, leading his children in the silence of melody out “to” worlds they would go on to make together. Deligny’s coordinates weren’t exclusively spatiotemporal; they were autistic. Unlike the dominant psychologies of his time, he resisted beginning his questions from what his kids were missing by not being able to speak. Instead, he wondered, what are we missing out by being able to speak? What does language obscure? As such, language wasn’t privileged in the camps; the children were not there to be helped and fixed. Instead, they were accompanied.

I started to accompany Deligny’s radical politics after staying with the question of responsivity in crisis-ridden times and seeking to articulate a politics of the common that might activate a meandering ‘chasmagraphy’ practice – a fugitive exile that deterritorialized heteronormative subjectivities and opened up elsewheres and otherwises. By thinking Deligny with black mattering, we might sense the outlines of a new politics – not one that necessarily replaces BLM or renders its crucial work moot and irrelevant, but one that reinvigorates it with a generative incompleteness, a gesture towards something else.

Reading Deligny’s inspiring guerrilla politics along with the bacchanal embarkations of a Yoruba trickster-god who teaches us that loss is the condition of life, along with an ontofugitive blackness that accepts the monster as an agency of social transformations, through the meandering spiritualities of my fatherhood and relationship with my autistic son, Kyah, and through the dense transversality of sitting with cracks, offers a humbling vision of an end-of-world network of arachnean sanctuaries practicing a Cevennean politics of descent. Of invisibility. Of Blackness as hiding – where hiding is not a want of courage but the gestational equivalent of wading in the water long enough to become-water in an era of rigid impasses and insurmountable struggles.

***

Do Black lives matter? Yes. Black lives shimmer with a recalcitrant light, the afterglow of generations of suffering and being put down. Black lives breathe and smile and sweat and dance and aspire and want and cry and hate and despair and do things. In this sense, we will need the politics of representation to notice the ways bodies are still excluded because of their identities. We cannot dismiss the need for recognition despite its hidden dynamics. Advocacy is critical.

An equally significant question, however, threaded through this text, has been: does black matter live? This is the mattering that stretches the thesis of Black discourse from the isolation of questions about recognition to questions about how the very detail of our living colludes with the hidden curriculum of white continuity. It means we cannot stop at justice, at representation, at the pearly gates of heaven. It is already time to cultivate this invisibility, to investigate the generosity of imperceptibility. To walk away. Walking away is not escape, it is exile. It is longing, it is cultivating imperceptibility, it is seeking allies that might help terra-bend ‘the world’ so it accommodates the queerness of black lives. Walking away is a matter of composting justice. We will need critique and the crossroads, the cross and the chiasmus.

We must travel.

We would need a cosmovision of exile, a go-bag, a shuffle in our feet, a song (ancestral in its contemporaneity), and a readiness to sit with the monster eggs gestating in our dehiscent claims to worthiness. Like the Yoruba god at the edges of the Atlantic, like the Xenomorph at the edge of civility, we would need to be quick – to steal into the cracks, to creolize the future.

It is at the edges that transformations happen. At the moment when our feet wade through the waters of the creek. At the threshold of the plantation. At the edge of the text. Beyond the intentions of the author, this one or any other one, we will turn. Birds aflutter where bipedal imperatives once ruled supreme.

“When all hope for release in this world seems unrealistic and groundless, the heart turns to a way of escape beyond the present order.”

Howard Thurman

Footnotes:

[25] In a different essay I am already swimming in the waters of, one I am yet to write, I address the “racist” as a cultural production of Cartesian metaphysics. Through this framework, inspired in part by Simondon’s transindividual thesis, I suggest that the ascription and reduction of agonistic tensions and affective intensities to an already composed individual person who is ‘racist’ is ironically a reinforcement of white modernity and its colonial project of thinking everything through the isolated self.

[26] Warren Smith, Matthew Higgins, George Kokkinidis & Martin Parker (2015): Becoming invisible: The ethics and politics of imperceptibility, Culture and Organization, DOI: 10.1080/14759551.2015.1110584

[27] Jasbir Puar, ‘I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess’: Becoming-Intersectional in Assemblage Theory. https://transversal.at/transversal/0811/puar/en

[28] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/mwazulu-diyabanza-netherlands-1936340

[33] https://culturalpropertynews.org/nigeria-welcomes-future-edo-museum-of-west-african-art-emowaa/

[36] By ‘worlding’, I mean to name the ways bodies and the relations that substantiate them are arranged in particular ways – to the exclusion of other possible modes of being convened. By thinking of the world as a “worlding”, an ongoing more-than-human process instead of a fait accompli only available for discovery, it becomes possible to disturb colonial claims to finality and investigate the ways much is excluded and flattened by the effort to associate the status quo with nature.

[37] https://www.economist.com/1843/2020/04/28/are-ghosts-haunting-the-british-museum

[38] https://www.economist.com/1843/2020/04/28/are-ghosts-haunting-the-british-museum

[39] Ontofugitivity is my theory of refusal, disturbance, and blackness that spills beyond the architecture of identity, beyond how it has been named, beyond the violence of its appellation. It is the idea of the nonsensible, ontology’s underground, the Simondonian transindividuality of things, the subterranean ontogenesis that crystallizes as crack or utility.

[40] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFYBg4c4lJk

[41] If contemporary activism retraces colonial lines in its quest for disembarkation, then it reproduces imperial cartographies. And what are bodies if not cartographies nested within cartographies, milieus entangled in milieus, intensities swimming in intensities, in dense palimpsests of reproducibility and potential errancy?

[42] Or a more-than-substantialist becoming that exceeds ‘being’ – how flows and lines spill beyond points.

[43] If you imagine this becoming-black as a Hiroshima-like explosion of sorts, then certain bodies – more than others – would be materially proximate to and im/mediated by the release of radioactive substances. This blackness-that-is-not-identity is the immanent ground of white coloniality, where the colonial names the material practices of staving off exposure to radioactive streams. A becoming-black is risking exposure, risking new shapes – which is not a choice per se, but an enablement, a gift of circumstance, always involving the monster. Becoming-black is a choreography of the monster. Becoming-black is not a ‘right’ of ‘Black’ people – even though the material histories, social hierarchies, and situations of some who identify as ‘Black’ might mean certain heritages of posture are easier to access.

[44] Nicola Perullo, ‘Aesthetics without Objects: Towards a Process-Oriented Aesthetic Perception’, Philosophies 2022, 7(1), 21; https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7010021

[45] Take a moment to watch the screen test for Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien…while it is still available, preferably at night – when the full impact of Badejo’s metamorphosis can creep up your skin and inseminate it with fear: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x4bw9gOy2Ps

[46] https://alienseries.wordpress.com/2014/08/23/the-life-of-bolaji-badejo-2/

[47] https://avp.fandom.com/wiki/USCSS_Nostromo

[48] https://www.inverse.com/article/31942-an-explanation-of-alien-covenant-xenomorph-biology

[49] https://www.inverse.com/article/31942-an-explanation-of-alien-covenant-xenomorph-biology

[50] https://www.inverse.com/article/31942-an-explanation-of-alien-covenant-xenomorph-biology

[51] Thanks to YouTuber ‘Novum’ for his video essay on the potential links between the Yoruba deity Esu and H. R. Giger’s Xenomorph, viewable here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tAsFCRshByY

[52] On a side note, I think it is very interesting that the Nostromo is sensitive to diversity, equity and inclusion! A Black man is part of the crew. Perhaps this speaks about the ways assemblage upsets intersectionality.

[53] Èsù, multiple and shapeshifting, defies gender categorizations, but is more popularly represented as a male figure in some stories I am familiar with.

[55] But it’s tiring, to say the least.

[56] I wish I could say more about what I mean by ‘Afrocene’, but I’m quite exhausted at this point.

[57] If it is not already explicit, I am reading ‘blackness’ closely with Gilbert Simondon’s ‘preindividual’ and Deleuze’s ‘plane of immanence’.

[58] I queer the word “peripheral”, infusing it with a vision of my autistic son and his visual imperatives in his ‘failure’ to look me in the eye. I call this ‘failure’ a “looking-away-at”, which lies somewhere between “looking at” and “looking away from”. Looking-away-at is an intelligence that sits at the crossroads between subject and object; it refuses to see the object as ‘object’, as stable, as merely outside its visual apparatus. Instead, it invites an aesthetic of flows, of becomings, of wild possibilities not available to looking straightforwardly at things. A peri-ferality.

[59] It is only individuated in the sense of already being a node of many crossings, a crystallization of effects that still necessarily touches an assemblage. There are no monsters in isolation. Even the Xenomorph is not monstrous to its offspring. Again, the monster is a pattern of relations crystallized as a crack, a resolution in the body of the unsuspecting citizen, an inseminated egg. The task of politics – I suggest – is to help this seminal transient gestate.

[60] The ‘crack’ is the crystallization of the monstrous, black mattering, and the promise of the exquisite – a site of looking-away-at, an aesthetic of touch without objects. Cracks are formulations that mark resolutions in preindividual flows that refuse the productivity of the surface, how monsters are individuated. They are sites of prophecy (by which I mean the way temporalities are simultaneous and nonlinear, and often convened again and again), of experiment, of autistic attempts.

[61] Dancing as a figure of postural metastability. As becoming-monster. Becoming-black is becoming-monster. This is a thick and dense site of postures, thresholds, intensities, and passages. It does not necessarily lend itself to matters of inclusion or exclusion; there is a spontaneity to it that suggests something is already happening with or without human sociality. In a sense, White people are already becoming-black, Black people are already becoming-black – though reterritorializations are always possible.

[62] Blackness as autistic meandering, not committed to creating new edifices may seem apolitical and antithetical to organizing, but this is the very stuff of exquisite shapeshifting: that politics is not necessarily about changing the world – as if the world were a uniform thing, giant and heavy, instead of subtle inflections resisting categoricity; it is about becoming-monster.

Báyò Akómoláfé is the Global Senior Fellow of the Democracy & Belonging Forum, where he acts as the Forum’s “provocateur in residence”, guiding Forum members in rethinking and reimagining our collective work towards justice in ways that reject binary thinking and easy answers. Learn more about his role here.

‘Part One' and 'Part Two' art modified from original by https://www.vecteezy.com/members/prawny