Bridging Divides Through Deliberation

Watercolor by Ieva Cesnulaityte

In 2025, in an era when the world continues changing at a speed where we can never quite metabolise emotions fast enough—feelings of fear, loneliness, and insecurity propel us to seek certainty and a sense of control. In Europe and North America, we too often attempt to cope by tapping into more of what tears us apart—competitiveness, adversarialism, exclusionary practices—reaffirming a false belief that a sense of security comes at the expense of others.

Our current democratic systems reinforce this winner-takes-all, so-called merit-based, elitist, highly competitive worldview. Elections, and the way that politics is generally conducted, enforces the belief that we need to argue and constantly fight to have a seat at the decision-making table. That only the loudest, richest, and the most assertive can be elected and lead. That we cannot trust each other and that there is no way of finding a solution that we can all broadly agree on.

These views create fertile ground for those looking for political gain by employing strategies that tap into our vulnerabilities and disillusionment. Authoritarian populist techniques that divide and exclude have proliferated, culminating in elected leaders that continue to build on fear and the othering of various social groups.

It is entirely possible, though, to imagine a democratic system built around belonging instead—one that responds to the very real needs we have for connection, agency, security, and dignity, and at the same time creates resilience against authoritarian populist tactics.

The quiet proliferation (1), over the past few decades, of citizens’ assemblies and other deliberative approaches to democracy are evidence of the reality of this different kind of politics. It turns out that bringing a randomly selected group of everyday people to learn, deliberate, and develop recommendations together leads to better policy decisions that better respond to the needs of all. It also shows us that it is possible to come to an agreement without disadvantaging, alienating, or leaving some groups behind. More broadly, this engaged and engaging way of decision-making implies that we are all capable, worthy, and valuable just because we exist. Each one of us has lived experiences that are a piece of the puzzle to our shared societal challenges.

This paper focuses on citizens’ assemblies as a bridging practice that builds the resilience of democratic systems. It focuses on examples from Central and Eastern Europe in particular, regions with recent legacies and, in some cases, present realities of illiberal regimes that would seem an unlikely setting for the current boom of citizens’ assemblies. It starts by contextualising the landscape of authoritarian populism in the region, then introduces citizens’ assemblies and juries as a remedial approach, and finally wraps up with three case studies in Hungary, Ukraine, and Lithuania (2).

Understanding the Landscape: Authoritarian Populism in Central and Eastern Europe

Juan-Torres González defines authoritarian populism as a form of politics that “combines features of populism and authoritarianism and is fuelled by nativism (favouring narrowly-defined “native” citizens over “outsiders”) and anti-pluralism (opposition to diversity)” (3). At the heart of the authoritarian populist strategy is the building of an in-group by strategically othering the “other/them,” and placing these groups in opposition and in competition with one another, specifically with the purpose of creating a sense of superiority and belonging for the in-group. Such techniques disguise the complexity of long-term problems by providing quick and easy solutions that falsely give people a sense of control and certainty, and hence provide a much desired temporary release from anxiety and fear for the in-group at the expense of the out-group.

Countries in Central and Eastern Europe are fertile ground for such divisive techniques to proliferate. Given the current geopolitical uncertainties–the full-scale war in Ukraine and Russia’s imperial ambitions—there is a real possibility of military intervention by a hostile neighbour in the region. This reality, unsurprisingly, exacerbates feelings of vulnerability, insecurity, and fear, and taps into existing collective trauma dating from the multiple decades of Soviet occupation and repression in most of the countries in the region. The totalitarian trauma of Soviet communism consisted of “Stalinist and post-Stalinist repression that lasted for almost 70 years in the Soviet Union and for over 45 years in the regions of Eastern Europe it had subjugated in the 20th century” (4).

Psychology professor Gailienė suggests that recent memory of the suffering caused by mass deportations, cultural colonisation, and forcibly seeded mistrust amongst citizens has left scars (5) that manifest in the form of low levels of trust, learnt helplessness (6) and low self-esteem, and more broadly a prevalent sense of unsafety. However, what remains intact is the powerful sense of self-preservation and a strong belief in the importance of freedom and independence that enabled these countries to regain their independence in the nineties. At the same time, the recent period of democratisation after the collapse of the Soviet Union presents a complex landscape with various degrees of democratic success—in some contexts democratic institutions remain weak, constitute avenues for corruption, and power is continuously co-opted, which presents structural disadvantages for democratic governance.

In the region, authoritarian populist political leaders often use these structural features, unresolved tensions, and feelings of fear for political gain, tapping into the need for belonging through exclusionary policies. In Hungary and Poland, for example, as researcher Marcoberardino suggests, migrant and LGBTQ+ communities are

continuously framed as threats to national culture and tradition (7). In Hungary, Slovakia, and Serbia, civil society groups and independent media are frequently labelled as disloyal, or foreign-influenced, by authoritarian populist political parties. Once in power, these parties champion and pass “Foreign Agent” laws in attempts to shrink civic space, as well as to control and delegitimize independent organisations and individuals that keep them accountable to society, observes activist Kirova (8). In the Baltics, Russian-speaking minorities and Roma communities are sometimes portrayed as threats to social cohesion or national security (9). These strategies foster division and mistrust, while reinforcing political control.

Importantly, the region is vulnerable to divisive othering strategies not only from authoritarian populists domestically, but also internationally, through Russia’s undue influence and hybrid war. Studies show that Russia “employs disinformation as one of its tools of hybrid warfare, adapting narratives to play on region-specific contexts, including ethnic, regional, and historical divisions” (10) aiming to sow mistrust and to fracture. This lays the groundwork for Russian-backed authoritarian populist leaders to gain power and distance Central Eastern European countries from the EU, its values, and eventually European allies, in the hope of regaining (what it claims to be as legitimate) influence in the region.

The Power of Deliberation and Sortition

Citizens’ assemblies, juries, and panels are a type of political institutions that offer conditions designed for constructive, thoughtful deliberation (11). Composed of randomly selected individuals who represent the diversity of society and are brought together to learn about a policy issue, deliberate, and develop recommendations, these deliberative processes have proliferated over the past few decades (12). Central and Eastern Europe in particular is experiencing a growing "deliberative wave" since 2016, where the number of countries implementing assemblies is expected to double by 2025 and reach 40 cases across the region (13).

There are two elements characteristic to citizens’ assemblies: sortition and deliberation.

Sortition is the method used to select assembly members through a lottery, ensuring that the group broadly reflects the demographic diversity of the wider population. This process usually unfolds in two phases: a first random invitation sent to a large pool, followed by a second lottery that ensures representation across key characteristics such as gender, age, education, and geographic location. This approach offers a radical form of equality: every resident has an equal chance of being selected, regardless of status or prior political involvement. By intentionally including people from all walks of life, sortition amplifies cognitive diversity, shown to be crucial in producing innovative and effective solutions (14), and ensures that those typically excluded from decision-making are given a seat at the table. To lower barriers to participation, assembly members are compensated for their time, and many other measures that enhance accessibility for all are put in place. The costs of these measures are covered by the public institution initiating them—a municipality, a ministry, or similar.

Deliberation is about collective reasoning grounded in learning, listening, and reflection. Unlike debate, which seeks to win, or dialogue, which aims merely for mutual understanding, deliberation encourages assembly members to examine evidence, consider alternative viewpoints, and work toward shared recommendations. It is a structured process designed to move beyond surface-level opinions, allowing for the development of considered public judgements. When citizens engage in such processes, especially within a randomly selected group, research has shown they feel more empowered and polarisation can be reduced (15).

How Citizens' Assemblies Work: Key Steps

Citizens' assemblies unfold through three carefully orchestrated phases, as outlined by DemocracyNext (16). Before the assembly, extensive groundwork establishes the foundation for success. This includes defining a clear purpose and mandate, setting up governance structures with commissioners and operators, and selecting a representative group of assembly members. Organisers prepare comprehensive learning materials, recruit diverse experts and stakeholders representing different perspectives and put together a facilitation plan that will take assembly members on a learning and deliberation journey that will end in concrete recommendations.

During the assembly, members engage in a structured learning and deliberation process that typically spans several weekends or sessions over months. The process begins with onboarding that helps them understand their role and builds trust within the group. Members then engage with high-quality, balanced information from experts representing different perspectives on the issue at hand. Through skilled facilitation, they move from individual learning to collective deliberation, identifying shared values and working through disagreements constructively. The process culminates in collaborative drafting of recommendations, with members voting on final proposals that reflect their collective judgment rather than predetermined positions.

After the assembly, the focus shifts to accountability and impact. Assembly recommendations are formally delivered to the commissioning authority, which provides a public response explaining how the proposals will be addressed. Regular follow-up ensures transparency about implementation progress, while evaluation reports assess both the process and outcomes. Critically, organisers provide ongoing support to assembly members, recognizing their significant contribution to democratic decision-making.

Belonging Through Deliberation

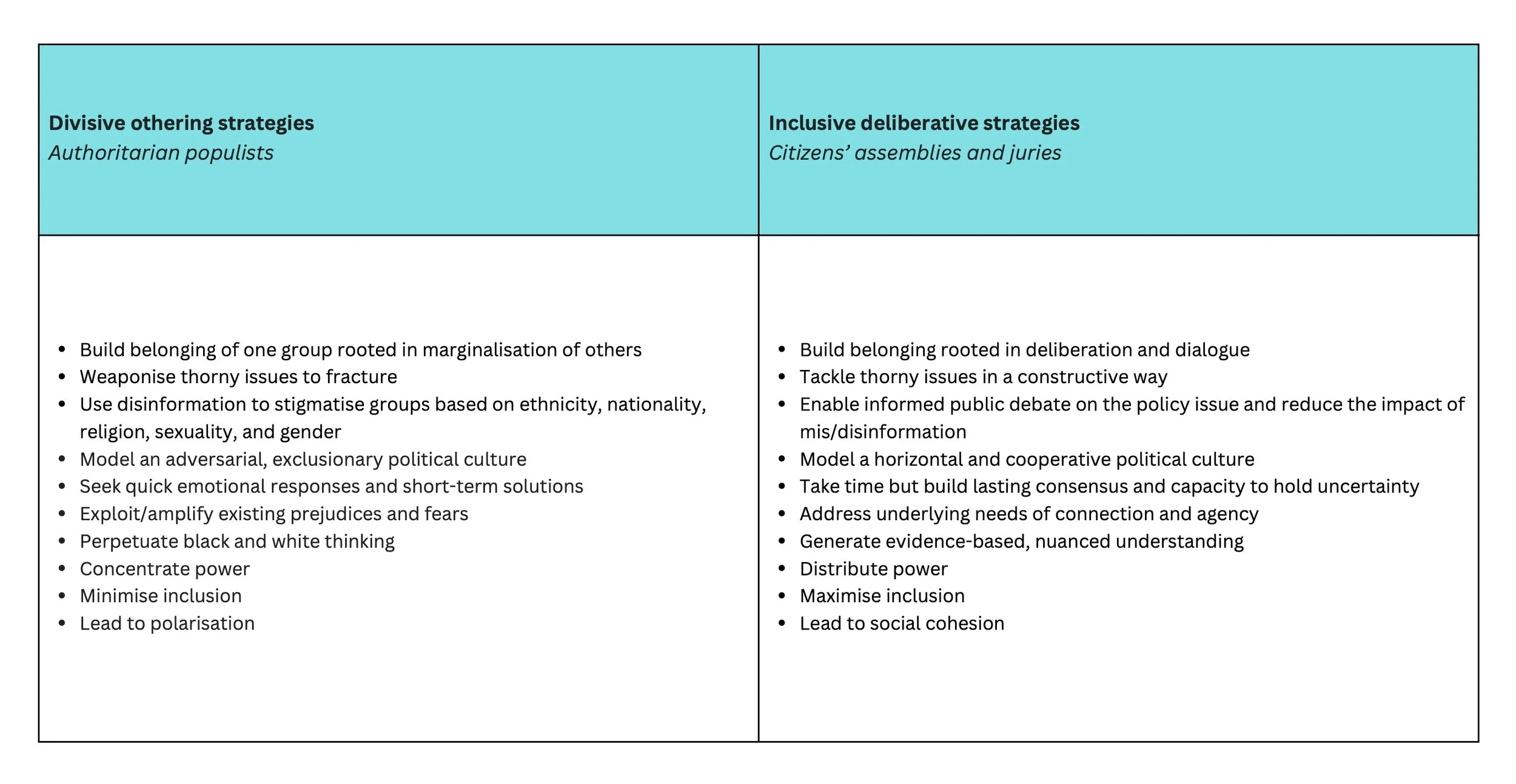

One of the missing ingredients in our democratic systems is harnessing belonging without tapping into othering and exclusion (17). Citizens’ assemblies are one of the constructive ways of building belonging that is rooted in deliberation, shared responsibility and mutual recognition, on top of the very real benefits for better policy and trust (Table 1). Because assembly members get a chance to meet and work with a highly diverse group of citizens from all walks of life, and have the time to listen to everyone’s point of view, they develop a nuanced understanding of the issue and witness the co-existence of a variety of realities. As they hear from stakeholders and experts, they become more informed and better able to question or justify their opinions. As they deliberate, they learn the skills of deep listening and respectful exchange. As they work through disagreements and tensions, they experience the possibility of constructive and inclusive solutions to shared problems. As they awaken the sense of agency in themselves—and feel it communally with others—their sense of hopelessness and anxiety about the future reduces. The sense of belonging builds, and is rooted in shared connection—not despite difference, but because of it.

Examples of Citizens’ Assemblies in Central and Eastern Europe

Even though the weight of the region’s past is still felt through the limited sense of citizen agency and trust (18), citizens' assemblies provide an avenue to strengthen and practice these essential democratic qualities through weaving a shared sense of belonging and a genuine opportunity for collective problem solving in a consequential way. They are part of a counter to divisive authoritarian populist narratives, telling stories of cooperative human nature and a hopeful future. Below are three of them.

Hungary (2023) | Újbuda Citizens’ Jury: Breaking Through Hungary's Participatory Deficit

Every morning, residents around Budapest’s Nádorliget housing estate faced the same frustration: gridlocked streets, circling endlessly for parking spaces, watching their neighbourhood choke on through-traffic. By June 2023, this daily aggravation had reached a breaking point. But instead of letting the issue become a source of community division, Újbuda district chose a different path—Hungary’s emerging practice of deliberative democracy (19).

In a country where Viktor Orbán’s government has steadily centralised power and marginalised civil society, deliberative tools remain rare. Only a handful of Hungarian municipalities had piloted citizens’ assemblies, making Újbuda’s democratic mayor’s decision to convene a citizens’ jury both locally necessary and nationally significant. The traffic problem around Nádorliget seemed perfect for deliberative treatment. It involved complex trade-offs between mobility, liveability, and sustainability that couldn’t be solved by technical fixes alone.

Over three days in June and July 2023, 36 randomly selected residents gathered at the local sports centre to transform individual frustrations into collective wisdom. The group represented the district’s diversity, creating opportunities for neighbours who might never otherwise meet to discover shared concerns across different backgrounds.

The process deliberately countered Hungary’s increasingly adversarial political culture. Rather than the zero-sum conflicts that characterise much of Hungarian public life, skilled facilitators from the Hungarian Association of Facilitators guided participants through collaborative problem solving. Expert presentations, from urban planners to transport analysts, provided high-quality information in 15-minute accessible formats, replacing the polarised narratives that dominate mainstream political discourse. Participants digested this knowledge together in small groups, building understanding rather than entrenching positions.

What emerged was both practical and transformative. The jury developed concrete recommendations: expanding bike-sharing systems, creating 30 km/h zones, redirecting through-traffic, and implementing smart parking tied to postal codes. But equally important were the relationships formed. Participants reported new friendships across different backgrounds, with conversations continuing informally over coffee and lunch.

Local politicians, including Deputy Mayor Richárd Barabás, attended the proceedings. The jury’s immediate legacy was clear: participants voted to initiate a larger citizens’ assembly on making the district greener, and the municipality committed to expanding deliberative tools. In a national context dominated by top-down governance, Újbuda demonstrated that Hungarian citizens, given the opportunity, could engage in the kind of respectful, informed dialogue that strengthens rather than divides communities.

The jury’s impact extends beyond traffic management. The Újbuda experiment offered a glimpse of democratic renewal at the grassroots level, proof that even in challenging political contexts, local authorities can become a line of resistance to authoritarian practices at the national level by opening up spaces for genuine citizen participation in shaping their shared future.

Ukraine (2024) | Slavutych Citizens’ Assembly: Democracy in Wartime

In October 2024, as air raid sirens occasionally interrupted proceedings, 45 residents of Slavutych gathered to tackle their city’s waste management crisis through Ukraine’s first citizens’ assembly. The timing was extraordinary. Deliberative democracy was taking root in a nation defending itself against authoritarian aggression, embodying the cooperative political culture that distinguishes democratic societies from divisive regimes.

Slavutych, built to house Chernobyl plant workers, had developed a strong civic identity that made it ideal for this democratic process. When residents were asked to propose topics for collective deliberation, waste management emerged as the winner. A complex issue crossing environmental, economic, and social lines that traditional politics had failed to address.

The assembly’s 45 members were selected by lottery from 167 volunteers, ensuring representation across all districts, ages, and backgrounds, including internally displaced persons. Over three autumn weekends, they moved through carefully structured phases of learning, deliberation, and decision-making. Expert presentations were balanced with field trips (including a visit to an innovative waste facility in Chernihiv) that grounded abstract policy discussions in concrete possibilities.

The process countered the divisive strategies that characterise both Russian disinformation and domestic populism. Instead of scapegoating particular groups for the waste problem, participants focused on systemic solutions. Instead of amplifying conflict between environmental and economic priorities, they sought creative integration.

By November’s end, the assembly had produced its recommendations: a weight-based collection system, a local recycling centre, expanded public education, and support for eco-start-ups. More importantly, it demonstrated how 45 strangers could become a deliberative community. Participants formed friendships across traditional divides, with 92% saying they would participate again according to the exit survey (20). Many expressed increased motivations for civic engagement.

The mayor and city council created an implementation working group including assembly members, giving the recommendations real pathways to policy. Initial steps began in early 2025, though some proposals require external funding that war conditions make challenging. In a moment when Ukraine is literally fighting for democratic values, Slavutych proved that inclusive deliberation can function even under the most difficult circumstances.

Lithuania (2025) | Vilnius Citizens’ Assembly: Reimagining Urban Mobility

In a city where Soviet-era planning still shapes daily commutes and climate goals clash with car-dependent lifestyles, Vilnius is preparing for Lithuania's first citizens’ assembly (21). By September 2025, 50 randomly selected residents will gather to tackle a question that affects every citizen's daily life: "How can we ensure that people in the city travel more often by public transport, on foot, or by bicycle, regardless of where they live?"

The challenge is both practical and philosophical. Vilnius already has a sustainable mobility plan extending to 2030, but implementation has been slow and lacks broad public support. City officials recognise that technical solutions alone won't transform how people move through their city; they need social consensus built through genuine participation. The citizens' assembly represents a radical departure from top-down planning, acknowledging that sustainable transport requires not just infrastructure but community buy-in across diverse neighbourhoods, from the historic centre to distant micro districts.

Over five carefully structured sessions from September to December, participants will journey from strangers to a deliberative community. The process is being designed to deliberately counter the polarised debates that typically surround transport policy: car users versus cyclists, centre versus periphery.

What makes this process particularly significant is its timing and scope. As Lithuania strengthens its democratic institutions against regional authoritarian pressures, the Vilnius assembly demonstrates how citizens can be trusted with complex policy challenges. The question itself, how to create sustainable mobility "regardless of where you live", explicitly rejects the exclusionary logic that leaves some neighbourhoods behind. By December, when assembly members present their final recommendations, they will have modelled the kind of inclusive problem-solving that democracy requires.

The real test will come after the assembly concludes. City officials have committed to reviewing recommendations through a formal process. But the assembly's deeper impact may lie in demonstrating that Vilnius residents, given quality information and structured dialogue, can transcend the usual conflicts over transport policy to imagine a city that works for everyone.

A Nuanced Picture

In Central and Eastern Europe, similarly to other contexts, citizens’ assemblies offer great promise but face real challenges. A core challenge lies in implementation of recommendations. Even though assemblies are usually initiated by institutional leaders such as mayors and ministers and produce thoughtful and broadly supported recommendations, there is no guarantee they will be adopted (22). Without legal mandates or institutional embedding, assemblies risk becoming symbolic exercises with limited long-term impact. This is particularly true in contexts where political will is weak, democratic institutions are under pressure, or public resources are constrained. Without follow-up, assemblies may inadvertently generate disillusionment rather than trust. However, they might still be worth the risk as they open up the imagination for new democratic ways forward and build capacity in citizens to deliberate, empathise, and listen; as well as capacity in institutions to engage citizens in a more genuine way.

In more politically restrictive environments, additional concerns arise. Assemblies could be limited to topics considered politically safe, such as traffic management or urban greening, while more sensitive issues, like migration and climate change, remain off the agenda. This selective approach can amount to participation-washing, where the appearance of citizen engagement is used to reinforce legitimacy without meaningfully challenging power structures. At the same time, in such contexts assemblies might open up an avenue of resistance against top-down national level authoritarian populism and strengthen democracies on the local level, which is often the last line of resistance (23).

Assemblies can also be subject to politicisation. They may be initiated for strategic purposes, criticised by opposition actors, or dismissed by those in power–all risks to their integrity (24). Public perception, shaped by media narratives, plays a crucial role in whether assemblies are seen as credible democratic practices. These risks make it essential to ensure transparency in how topics are selected, who initiates the process, and who is responsible for implementation. Observing international good practice principles (25) and involving international advisors or observers are helpful approaches to pre-empting such situations.

Yet the picture is far from bleak. Across the region, growing interest among local governments and civil society shows that momentum is building. Examples from other parts of the world provide inspiration: some governments have begun institutionalising citizens’ assemblies as a regular part of the democratic infrastructure. From Paris and Brussels to Bogotá and Ostbelgien, assemblies are no longer one-off practices but are increasingly embedded in public decision making (26). Embedding assemblies in municipal frameworks, ensuring transparency, and creating follow-up mechanisms can help bridge the gap between participation and policy impact.

Conclusion

At a time when authoritarian populists exploit our need for belonging, security, and agency, citizens' assemblies offer a fundamentally different path forward, creating space for genuine connection rooted in shared problem-solving rather than exclusion and othering. The experiences across Central and Eastern Europe demonstrate that even in contexts shaped by historical trauma and contemporary geopolitical pressures, ordinary citizens can transcend division when given structured opportunities to learn, deliberate, and create together. Though challenges remain real, the momentum is undeniable as these practices proliferate. Citizens' assemblies offer hope precisely because they address the root causes rather than the symptoms of democratic crisis. The region that knows both the costs of authoritarianism and the possibilities of democratic renewal may well lead the way toward a more deliberative, inclusive, and resilient democratic future.

Endnotes

The author has been advising on the design and implementation of the first Citizens’ Assembly in Lithuania on behalf of an international research and action institute DemocracyNext. Learn more about DemocracyNext’s Cities Programme https://www.demnext.org/projects/citiesprogramme

OECD, Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions.

DemocracyNext, Assembling an Assembly: A How-to Guide (2023), https://assemblyguide.demnext.org/.

OECD, Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions.

Author bio:

Ieva Česnulaitytė is a researcher, policy analyst, and activist specialising in democratic innovation and citizens’ assemblies. She has worked across government, civil society, and international organisations, including the OECD and DemocracyNext, leading projects and developing key resources on deliberative processes. Her recent research explores the intersection of deliberative democracy and collective memory. Ieva advises on citizen participation globally and is currently working the first Citizens’ Assembly in Vilnius, Lithuania, taking place this autumn. More about Ieva’s work: https://cesnulaityte.com

Editor's note: The ideas expressed in this blog are not necessarily those of the Othering & Belonging Institute or UC Berkeley, but belong to the authors.