Radical inclusion as an antidote to othering- Fryshuset’s methods for making youth feel like they belong

Inga Israel for OBI x Fine Acts

In the early 1980s, Stockholm residents grew increasingly alarmed about clusters of teenage boys and young men with shaved heads and military boots in Stockholm’s historic Old Town quarters. Skinhead culture, originating from the UK, was not necessarily connected to white supremacy—but some parts of Stockholm’s skinhead subculture had begun to be heavily influenced by neo-nazi ideas and music.

In other parts of the inner city, not far from the Old Town, and coming from the immigrant-dense, lower-income suburbs, different groups of youth likewise began gathering in the evenings and on weekends. Around this time, immigration to Sweden had shifted from being composed mostly of labor migrants from Southern European countries, to including more asylum seekers from the Middle East, the former Yugoslavia, and Northern Africa. Before long, fights began erupting between groups of immigrant youth and skinhead youth. It was in this context that Fryshuset was born–an NGO with a mission to be a place where all young people, regardless of background or personal history, would feel welcomed and find belonging through shared passions.

In a move that was controversial then, and would likely still be today, founder Anders Carlberg decided to open the doors to Fryshuset and offer a safe space for skinhead youth. He operated on the conviction that if someone showed these young people that they were wanted and welcomed, they would eventually turn away from violence and destructive rhetoric and actions. At the same time, Carlberg and his colleagues also invited young people with immigrant backgrounds, equipping them with tools for becoming leaders for nonviolent action. Where others saw just violent young people, Carlberg saw lost boys with little hope for the future and no adult mentors, who had channeled their disillusionment into anger, hate and violence. To close the doors to them would further add to their convictions that they were cast aside by mainstream society and fuel their disillusionment and hate.

Fryshuset has since become Sweden’s largest youth organization and an important actor for bridging and belonging initiatives. Its operating assumption is that the joy of engaging in shared passions will serve as a means for bridging differences and create shared hope for the future. Focusing on reaching those who feel like they do not belong in mainstream society, Fryshuset’s approach is that of radical inclusion—where every person is granted a second chance. Engaging those who are often seen as the problem, such as young people drawn into criminal gangs or radicalized movements, the organization aims to bolster young people’s hope for the future by providing every individual with the conditions to feel seen, loved, and included in society. Fryshuset trusts that all youth, provided with the right support and skills, will go on to lead positive change in their own lives and in society.

Political context

At home as well as abroad, Sweden is often perceived as a tolerant social welfare state that champions equity and inclusion. The “Swedish model” was built on democratic movements advocating for fair labor laws, collective agreements, and social welfare, laying the foundation for a lasting dominance of social democratic policies in the 20th century. The aim was to build a society inclusive of all.

In the past three decades, the country has welcomed a proportionately large number of asylum seekers, thanks to a generous migration policy rooted in both labor needs and humanitarian frameworks. This has radically changed Sweden’s demography, with 20% of the population having been born outside Sweden, and 60% of whom were born outside of Europe. The largest groups of non-European immigrants come from Syria, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia (1). After the 2015 refugee and migration crisis in Europe, Swedish migration policy was restricted, significantly, reducing the number of asylum-seeking immigrants from non-European countries.

Over the same time-period, socio-economic residential segregation (2) in Sweden has increased and often overlaps with ethnic residential segregation, a situation where residential areas that have a majority of residents with an immigrant background tend to be poorer than the national average. Notably, reports have shown that growing up in a low-income area has a correlation to lower levels of education and income later in life (3). Whilst affluent areas have grown in number, poorer neighborhoods have also increased, and many so-called “vulnerable areas” have evolved. These areas are defined—namely by the police—as having low socioeconomic status and a prevalence of criminal activity that directly impacts the local community (4).

Concurrently, Sweden has seen a rapid and alarming rise in gang-related deadly crime and now suffers from the second-highest gun crime death rate in Europe, much of which has been concentrated in these “vulnerable areas.” While criminologists are broadly in agreement that growing income inequality and poverty are at the root of this development, competing narratives that ascribe the violence to ethnic and religious factors have gained wide popular support (5).

One of the key proponents of such narratives is a nativist political party—the Sweden Democrats—which, over the course of the 2020s, has grown to become Sweden’s second largest party, winning some 20% of the votes in the 2022 elections. A third of the party’s founders have documented historical ties to far-right and/or nazi movements (6). The Sweden Democrats have built large parts of their political agenda on a narrative of having long-warned about problems in immigrant-dense areas. They also describe the Swedish welfare system as having collapsed, blaming immigration for it. The Sweden Democrats are advocating for policies such as repatriation programs for immigrants, and other proposals that they see as necessary to “make Sweden good again” (7).

Fryshuset’s early history and work with skinhead youth

In 1984, as concern about skinhead culture and friction between skinheads and immigrant youth was mounting in the Swedish public sphere, Anders Carlberg was volunteering as a basketball coach with the Swedish YMCA. During his work as a construction foreman he would look out for places to build more courts for the club’s players. When he finally found an old cold storage warehouse, he decided to turn it into a space for basketball courts, but also equipped it for concerts and outfitted more than thirty music rehearsal spaces. A few of his construction workers were also musicians, and had shared that they were always looking for places to rehearse. He called the place Fryshuset (“the cold store”).

Carlberg was a well-known leftist political activist and had been one of the leaders of a 1968 occupation of a student union building, protesting educational reforms that were perceived as granting the state too much power over universities. Though the initial idea for Fryshuset was to offer youth in Stockholm more space for sports and music, Carlberg soon realized that it could become a platform of wider societal engagement for youth, advancing his vision for a more fair, inclusive, and less segregated society.

When violent riots and brawls began to break out between large groups of skinheads and groups of immigrant youth from the outskirts of the city, Carlberg set in motion one of Fryshuset’s first social projects, as an explicit attempt to reduce the violence. The project, Non-Fighting Generation (NFG) recruited youth from some of the violent groups—mainly with immigrant backgrounds—to become non-violence role models for other youth. Parallel to this, Fryshuset launched an annual music festival called “Ten Last Days” to provide a positive environment for youth during the last ten days of the summer break—a period when fights and riots tended to increase." The festival still exists today under the name We Are Stockholm.

Anders Carlberg went on to raise funding to build a new building, where he invited skinhead youth to come and hang out as an alternative to gathering in Stockholm’s old town. He believed that if young people did not feel included in mainstream society, their innate urge to belong would drive them to find belonging through othering, in destructive environments fueled by anger and hate. Carlberg wanted to show the skinhead youth that they were welcomed at Fryshuset, with the hope that by spending time in a safe space and engaging in activities with other young people who were not like them—such as youth with immigrant backgrounds—they would slowly begin to shift perspectives and see that living together was possible.

Patrik Asplund, a prominent leader in Stockholm’s skinhead subculture at the time, says that what was truly remarkable for him and his friends was that “someone (grown up) seemed to care about us” (8). When everyone else made it clear that the skinhead youth were not welcomed, Anders Carlberg’s willingness to build relationships with them and offer them a place to be was unique. Patrik tells of a time when he had to ask someone in the gym to help him with some weights, and the only person available was a young Black man from Easy Street (Lugna Gatan), a social program at Fryshuset serving mostly youth with an immigrant background (9).

Slowly, a certain respect between previously separate groups began to build, initiating meetings and relationships that would have been unthinkable outside of the walls of Fryshuset. In 1998, Patrik eventually decided to disengage from the white supremacist part of the subculture and took part in starting Sweden’s first disengagement program, EXIT, at Fryshuset. He has since turned running a variety of inclusion and integration programs for youth into his life’s work.

Tensions would sometimes run high, and at times fights broke out between the various groups at the center. In one room some youth might be playing music with white supremacist messaging, whilst in another some of Sweden’s earliest hip hop music was being produced by youth with immigrant backgrounds. Still, Carlberg’s vision of creating a movement where everyone felt welcomed and could meet across group-lines through sports and music continued to attract young people from different parts of Stockholm. The activities that they could get involved in grew to include martial arts, skateboarding, dance, music production, and more.

A lasting outcome from those early days is Fryshuset’s disengagement program EXIT, which pioneered a method for how to work with individuals who wish to leave radicalized movements. Emerich Roth, an Auschwitz survivor who spent years working with Anders Carlberg, was part of its creation. He believed that radical inclusion was the antidote to radicalized movements that were based on belonging through othering. EXIT’s methods have been adopted by many other actors in Sweden and abroad. Today, EXIT not only works with individuals who wish to leave white supremacy but also other kinds of radicalized groups, such as people returning after having joined ISIS.

Fryshuset’s stance for radical inclusion

Fryshuset has often attracted criticism—from all sides of the political spectrum—for being too tolerant and inclusive of youth with radical and sometimes violent ideological convictions. For its part, the organization has held firmly to its guiding principles, which state that it should be at the forefront of societal challenges facing youth and approach those who do not feel they belong in society with courage, openness, and empathy. Where others tend to shun away, Fryshuset dares to stand fast, trying different ways to reach those who are difficult to reach, and seeing opportunities where others tend to see problems. The organization sees extending love and an unwavering faith in people as its task, to enable everyone to rise by providing the right support and environment to grow and thrive (10).

In a 2014 op-ed in response to an anti-nazi demonstration in Stockholm, current CEO of Fryshuset Johan Oljeqvist criticized that action for being counterproductive. He argued that history has shown that excluding and condemning those deemed as “undesired” only confirms their raison d’être and fuels their growth, attracting new followers who feel equally cast aside by the perceived majority or elite. Concerned by the fact that it is more common to see initiatives that deepen societal divisions rather than promote mutual understanding, he called for a movement that embraces and includes everyone, even the hateful and fearful. He argued that such destructive expressions will not survive in an environment of acceptance and inclusion (11). The article garnered strong criticism from people who found the notion of embracing and including people with neo-nazi convictions unacceptable and immoral.

With a mission “to enable youth to change the world through their passions,” Fryshuset has since grown into one of Sweden’s largest NGOs. Now housing Europe’s largest youth basketball club and offering a dozen “passions” for youth to get involved in, the organization also operates more than 60 social programs in areas like youth leadership, interreligious dialogue, entrepreneurship, disengagement programs for youth in criminal gangs—and also runs its own schools. Fryshuset has seven locations in Sweden, collaborates with youth organizations internationally, and has given rise to sister organizations in Denmark and Norway. It employs around 1,000 people and has 2 million meetings annually with youth.

Towards a wider sense of belonging: in-group approaches as a first step

In polarized environments, various movements often turn to single or shared identity spaces to provide a sense of immediate safety. Fryshuset’s experience speaks to the understanding that such spaces stand-alone do not advance inclusive social structures that address the needs of all communities. Building meaningful relations across divides requires a push beyond these spaces and the facilitation of meetings that will often bring discomfort, disagreement and even a sense of insecurity.

However, when working with individuals and groups who may have been radicalized to a point where they do not regard the “other” as fully human (“they are not like us”), or that experience a high level of fear or discrimination as part of a minority group, Fryshuset has found that the inward-focused approach is often a necessary first step. Members of these target groups are not always ready to be thrown into the insecurity and discomfort of meeting across group lines. To get there, they need a preparatory process that builds courage and a level of openness and curiosity to meet the unknown, or “the other”.

Fryshuset runs many in-group youth programs that are single or shared identity spaces, such as the “United Sisters” and “United Brothers” programs. Focusing on reaching girls and boys who experience marginalization, discrimination and low self-esteem, these groups attract youth who do not have a group or community where they feel safe and like they belong. They often express low trust in society and its systems, making them difficult to reach for actors such as social services. As a non-state actor, Fryshuset is sometimes more successful in building an initial relationship and trust with these youth. The programs offer youth a mentor, and skills in self-leadership, whilst building relationships with others who they can recognize themselves in.

For youth whose disillusionment with society and search for belonging has led them into radical environments such as white supremacy movements or criminal gangs, Fryshuset offers disengagement programs. Some of the programs require a willingness to disengage from radical or criminal environments, while others focus on motivating individuals who are at risk of entering such environments to choose a different path. Through intense one-on-one mentoring over longer periods of time, individuals are supported and motivated to leave the destructive environments they have been drawn into, and take the first steps towards a positive, non-violent way forward in life.

Credible messengers and the importance of skilled youth workers

Supporting youth on the journey from feeling like an outsider to feeling like they belong in society requires active mentorship from skilled youth workers. Inclusion does not just happen passively; it needs to be facilitated to continuously bolster hope and resilience and build courage to step outside of one’s comfort zone.

Simply putting out an ad that there is a youth program looking for participants is not enough to reach and recruit youth who have a general lack of trust in society. Active outreach is required, with a heavy emphasis placed on trust and relationship building with the target group to motivate them to get involved. For this task Fryshuset often employs so-called credible messengers as youth workers for its various programs. Fryshuset’s definition of a credible messenger is someone who, thanks to specific experiences and qualifications, can reach and build trust and relationships with target groups that other actors such as state agencies find difficulty engaging with. Credible messengers have often grown up in similar circumstances as the target group, or have in other ways earned a deep sense of understanding of their lived experiences. Most single or shared identity programs at Fryshuset are led by youth workers who are credible messengers. All credible messengers are paid employees at Fryshuset. They serve as role models and mentors and are paramount in bringing youth from spaces of distrust and disillusionment to a sense of belonging and willingness to participate in society.

From in-group approaches to cross-group bridging–Fryshuset’s participation model

In 2012 Fryshuset started a youth leadership program called Mpower, in partnership with the Swedish Women’s Voluntary Defense Organization (Svenska Lottakåren). In and of its own, the collaboration was a bridge-building exercise. The two organizations came from different contexts; Lottakåren traditionally attracts youth from a more affluent background, often representing an ethnically Swedish demographic who come to learn about contingency and crisis management, and Fryshuset, who focuses on engaging youth from marginalized communities in their programs, often attracts youth with an immigrant background.

The Mpower program welcomed young men and women aged 18-24 to spend three weekends learning about leadership, crisis management and community resilience, and was financed by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB). The goal was to create a more resilient Sweden by empowering youth to become agents for inclusion and positive change in their own communities.

Understanding social cohesion as a key ingredient to building a resilient society, Fryshuset and Lottakåren saw the need to bring together youth who would otherwise not meet across ethnic, geographic, and socioeconomic lines. They wanted to create a shared sense of belonging that would motivate collective action towards a safer future together. Fryshuset reached out to some of the youth groups that were active within the organization at the time to find participants. The youth workers leading the groups identified youth who they thought would be willing to take a step outside their comfort zone and participate in the program.

On the day of departure to the program venue, a remote countryside location, the organizers found that some participants from Fryshuset’s groups failed to show up and were difficult to reach. This puzzled the organizers: when they had met the youth in their groups with their leaders, they had shown a lot of enthusiasm and seemed eager to participate in the Mpower program. What had happened between then and the day of departure?

By interviewing the youth and the youth workers in the Fryshuset programs, it became evident that though the single or shared identity groups filled the important need of creating inclusive and safe spaces, they did not always do enough to encourage youth to take the next step into what was still unknown, such as going to activities outside of their own neighborhood or province, or meeting people who had a different background than their own. The empowerment nurtured within these groups needed to be followed by a challenge to push beyond the safety of the in-group and by the close mentorship of the youth worker leading the group.

The learnings from Mpower led to the development of Fryshuset’s Model for participation (Fryshusets delaktighetsmodell).

Fryshuset’s Model for participation (Fryshusets delaktighetsmodell) (12)

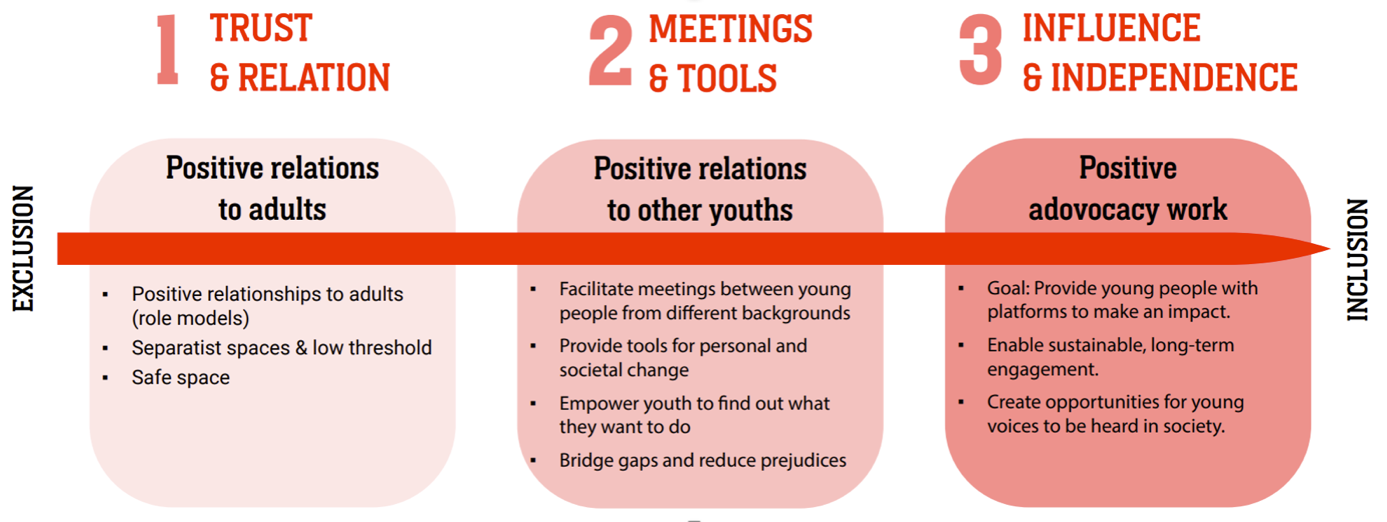

The model determines where a young person is on the “scale of inclusion”, represented by the red line, and which program or intervention might suit them best according to their needs. Someone who feels like an outsider to society and who often experiences a high level of mistrust towards the adult world places far left on the scale. For them, a low-threshold program, or a “Step 1-program”, might be best suited. In a Step 1-program, the focus is to build positive and trusting relationships with youth workers who act as role models (often credible messengers) in a group environment where the young person feels safe. This is often a “separatist” group, which means it brings together young people that have a shared identity based on gender, experiences, or other background markers, depending on the purpose of the program.

Once a young person has moved along the scale of inclusion, they are ready to be challenged into a Step 2- program where they build positive relations with other youths that are dissimilar to themselves, expanding their comfort zone by learning skills for personal growth and societal change. This can be in the context of a program such as Mpower, where alongside training in contingency leadership, meetings and dialogue with youth from different backgrounds are facilitated throughout the program. This is a space where prejudice and fears of those different from oneself can be challenged.

In Step 3 of the model, youth are further empowered and supported if they wish to make an impact on a societal level. For example, this can be through a leadership program in political advocacy or training in project management.

The model clarified that some of the youth they had recruited for Mpower were in Step 1 of the model, with little preparation for how to move on to Step 2. This was holding them back from showing up to the program. Keeping youth in Step 1 and focusing on in-group bonding for too long could lead to a stagnation in their democratic and social development, preventing them from independently engaging with people from different demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds. The youth leader would not always be there to provide a safe space, and at some point, they would need to face the discomfort and insecurity of meeting others who they saw as different from themselves. Seeing that true safety is built on a shared sense of belonging with people outside of the in-group, Fryshuset saw a need to begin actively supporting youth to move outside of their single and shared identity groups.

One simple action that made a big difference was that the youth workers in each program would accompany the young participants to the train station on the day of departure to the program venue. This action enabled youth to dare take the first step into the unknown, eventually moving them along the line of inclusion into Step 2 and creating a wider sense of belonging that reached outside of the comfort zone of their local community.

Case study: Building coalitions across group-lines in Östra Göinge

In 2020, Fryshuset was running a youth center in Östra Göinge, a small, rural town in the south of Sweden. The central organization had learned that there were growing conflicts between the two main target groups that visited the center; one with predominantly ethnically Swedish youth who attended the center’s garage and motor vehicle activities, and the other with youth of immigrant background who attended activities in another part of the building. Tensions were running high as both groups expressed that the other was having prejudiced and hostile attitudes towards them. The unspoken rule was that the invisible line between the two sides of the center was not to be crossed.

The organization decided to create an intervention based on the model for participation to motivate youth from both sides of the center to meet and interact in a facilitated way and hopefully find more positive ways to relate to each other. A youth-led initial mapping of the situation showed that most youth at the center were in Step 1 of the model for participation: they attended programs based on what they were passionate about, where they had found a safe space with a youth worker that they trusted and with youth who they perceived were like themselves. The mapping also showed that there was widespread prejudice and fear of the “other” in both groups, with conflicts sometimes erupting. To move youth into a wider sense of shared belonging with the group on “the other side” of the center, there had to be a process that challenged them to step out of their comfort zones and engage in joint activities that would enable them to forge new relationships with each other.

Designing an intervention based on the credible messenger approach, Fryshuset identified three young leaders from each group. The group of young leaders was chosen to represent both girls and boys and selected based on their ability to act as role models and build trusting relationships with their peers in each group. The group of young leaders were offered an hourly salary to work with the intervention. The first activity was for the group of young leaders to attend a 5-day training in Dialogue for Peaceful Change (DpC), a conflict transformation and mediation method stemming from the Corrymeela peace center in Northern Ireland (13), at a venue far from home, together with another 10 young people from other parts of the country. Among other things, the training involved understanding how and why conflicts arise, how people react to them, and how to map out conflicts. It also involved intense practice in a six-step mediation process through role-play, certifying the participants as facilitators of mediative dialogue. The goal was to provide the young leaders with a shared set of tools to handle conflicts that could arise between the divided groups back home. An equally important goal was to encourage closer relationships between the youth leaders to enable better collaboration for the task ahead, by letting them live together for five days, training, eating, and socializing together and sharing stories about their upbringing and background.

Under the mentorship of a senior youth worker, the group of young leaders spent the next couple of months designing activities to facilitate meetings between the two divided groups at the youth center. They started small, with a FIFA video game cup at the center, working hard on motivating youth from both sides to join. Towards the end of the project, a large paintball tournament was arranged, where about 20 participants from both sides signed up. They were divided into two teams that were purposely mixed across group lines. With time, some youth with immigrant backgrounds began showing up to some of the activities at the garage, where their shared passion for cars and motor vehicles served as an entryway to deeper sharing and dialogue.

Gradually, new relations formed, and the young leaders could sense a noticeable shift at the youth center. People had become friends across group lines, and though conflicts and prejudice still existed, there was a sense that more people were prepared to stand up for the “other” side and dare go against the norm of separation. The young leaders reflected that this change had the potential of being long term. They also said that it wouldn’t have been possible hadn’t the group of young leaders gone through their own initial process of learning new skills together to navigate conflict and change, where they also got to know each other better and began to build a level of trust and understanding.

An ongoing need for radical inclusion and Fryshuset’s model

The relevance of Fryshuset’s work in the Swedish context remains high. Youth who live in “vulnerable areas” often express that they do not feel like a part of Swedish society, a sentiment that can lead to dangerous disillusionment and lack of hope for one’s own future—pushing some into destructive environments. In other parts of Sweden, a movement of so-called “active clubs” has grown. They are informal, social networks that base their ideology on right-wing nationalism, drawing mostly teenage boys and young men to meet and practice martial arts and fighting. Members express that they have lost faith in the democratic system and that they are prepared to use violence to further their political agenda. The Swedish security services estimate that there is an active club in every one of Sweden’s 140 municipalities (14).

The need for bridging and belonging can be seen across other lines of separation as well. This spring, in the context of the ongoing war in Gaza, Fryshuset youth leaders in Malmö facilitated a safe space for youth with a Palestinian background and youth from a Jewish organization to meet in dialogue. Though many were hesitant to show up, some eventually trusted the youth leaders enough to attend. The dialogue was honest and sometimes tense. Afterwards, many participants reported that though they did not always agree with the other group, they could see that they shared more similarities than they had previously thought.

Fryshuset’s approach of radical inclusion is realized through its model for participation and work with credible messengers, actively finding and motivating youth who have become disillusioned with society and who feel like outsiders. By always leaving the door ajar, the message is that you are always welcome at Fryshuset. Knowing that it is scary and difficult to step into the unknown, Fryshuset actively supports youth to dare to take that step, and offers a second chance to those who might once have gone down a destructive path. The belief is that all young people, once they feel a wider sense of belonging and feel seen and loved, will become powerful agents for change and create a more inclusive and sustainable society for all.

Endnotes

1. Järvaveckan, Svensksomalierna – mellan stigmatisering och samhörighet (Stockholm: Järvaveckan, 2023), 16, https://jarvaveckan.se/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Svensksomalierna.pdf.

2. Delegationen mot segregation (Delmos), Segregation i Sverige: Årsrapport 2021 om den socioekonomiska boendesegregationens utveckling (Huddinge: Delegationen mot segregation, 2021), 29, https://segregationsbarometern.boverket.se/app/uploads/2024/09/Segregation-i-Sverige_Arsrapport-2021-om-den-socioekonomiska-boendesegregationens-utveckling_Delmos-2021.pdf.

3. “Rapport: Uppväxtområdet avgörande för framgång senare i livet,” Dagens Nyheter, September 25, 2024, https://www.dn.se/sverige/ny-rapport-uppvaxtomradet-avgorande-for-framgang-senare-i-livet/

4. TT, “Över 700 000 bor i utanförskapsområden,” Omni, November 13, 2024, https://www.omni.se/ny-rapport-over-700000-bor-i-utanforskapsomraden.

5. Viktor Sunnemark, “How gang violence took hold of Sweden – in five charts,” The Guardian, November 30, 2023, last modified January 16, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/30/how-gang-violence-took-hold-of-sweden-in-five-charts.

6. SD:s vitbok: Var tredje grundare kopplas till nazism eller fascism, Svenska Dagbladet, June 26, 2025, https://www.svd.se/a/mrAl8O/sd-s-vitbok-var-tredje-grundare-kopplas-till-nazism-eller-fascism.

7. Sverigedemokraterna, “Vilka vi är”, accessed May 10, 2025, https://www.sd.se/vilka-vi-ar/

8. Interview with Patrik Asplund, by Sarah Nilsson Dolah, May 29, 2025.

9. Ibid.

10. Fryshuset, "Our Core Values," Fryshuset, accessed June 1, 2025, https://fryshuset.se/english#core-values-in-depht

11. Fryshusets vd: Demonstrationen mot nazisterna var felriktad. Dagens Samhälle. June 11, 2014, https://www.dagenssamhalle.se/styrning-och-beslut/demokrati/fryshusets-vd-demonstrationen-mot-nazisterna-var-felriktad/.

12. Fryshuset’s model for participation was first created by Kathy dos Santos Gillberg and Maj Pettersson

13. DpC Global, "About," accessed June 3, 2025, https://www.dpcglobal.org/about.

14. Annika Andersson, "Aktivklubbarna växer sig starkare – en miljö som föder våld," Dagens Nyheter, July 4, 2025, https://www.dn.se/sverige/aktivklubbarna-vaxer-sig-starkare-en-miljo-som-foder-vald/.

Author bio:

Sarah Nilsson Dolah is a political scientist, educator, and facilitator of mediative dialogue, who has spent seven years at Fryshuset developing projects that implement international peace building and dialogue methods in the Swedish context. A heavy focus in her work has been on crime prevention and supporting youth workers who in turn work with youth that have been drawn into destructive environments and criminal gangs. Sarah is also active as a freelance consultant in the fields of peace building, conflict resolution, dialogue facilitation, and change management. She has an MA in Politics and War from the Swedish Defense University and a bachelor in Political Science from Macalester College, USA. She is a coach in Dialogue for Peaceful Change (DPC), a method in conflict resolution and mediation from Corrymeela Peace Center in Northern Ireland, and has been responsible for bringing this method to Fryshuset and establishing it in the Swedish context.

Editor's note: The ideas expressed in this blog are not necessarily those of the Othering & Belonging Institute or UC Berkeley, but belong to the authors.